Gatorade: Building On 50 Years of Innovation

On March 29th, 2015, I ran my first marathon in Ormond Beach, Florida.

I had started running just one year prior, decided to try for a marathon, bought a how-to book, trained for 18 weeks, and endured grueling runs after work and on weekends.

Finally it was here. The race started at 6:30 a.m. I was excited, nervous, worried I might not finish.

I remember checking my GPS watch early on … 0.2 miles down, 26 to go. My pace was good through the first few miles, on target through the midpoint, then fell apart at mile 17 and beyond. But I finished!

Three things kept me motivated during the race: the satisfaction of finishing, a kiss from my wife as I crossed the finish line, and an ice-cold Gatorade in a cooler in my car.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the invention of Gatorade at the University of Florida, an event that changed UF forever.

The story of Gatorade begins with a simple fact that is as true today as it was in 1965 – it is unbearably hot and humid in Florida from mid spring to late fall.

In the early 1960s, the University of Florida had a good football team, but with each practice and home game they had to battle an opponent besides the other team – the unrelenting heat and humidity. It took its toll on the young men every time they took the field. Back then, there was little appreciation for the challenges and dangers of heat injuries.

In fact, many coaches discouraged players from drinking any water during practice.

Assistant football coach Dwayne Douglas saw this problem every day, so one day in August 1965 after several players had to be admitted to the Infirmary for heat exhaustion and dehydration, he sought advice from his friend Dr. Dana Shires, who brought it to the attention of his major professor, Dr. Robert Cade, a UF kidney specialist.

Now the story of Gatorade could have ended right there, but when talented people like Robert Cade are presented with unanswered questions, they are driven to find solutions.

Cade, Shires and two other research fellows – James Free and Alejandro de Quesada – met with Gator coaches and trainers and formulated a plan, but it involved using players as test subjects. Head Football Coach Ray Graves agreed to let the doctors work with the freshman team, but the varsity players were off limits.

Cade and his team went to work. They collected sweat, drew blood samples and measured vitals and performance for the freshman football players, seeking to understand the physiological changes they were experiencing in hot, humid Florida. The results were eye-opening. The players’ electrolytes were completely out of balance, their blood sugar and their total blood volume was low.

The impact on the body of this upheaval in chemistry was profound.

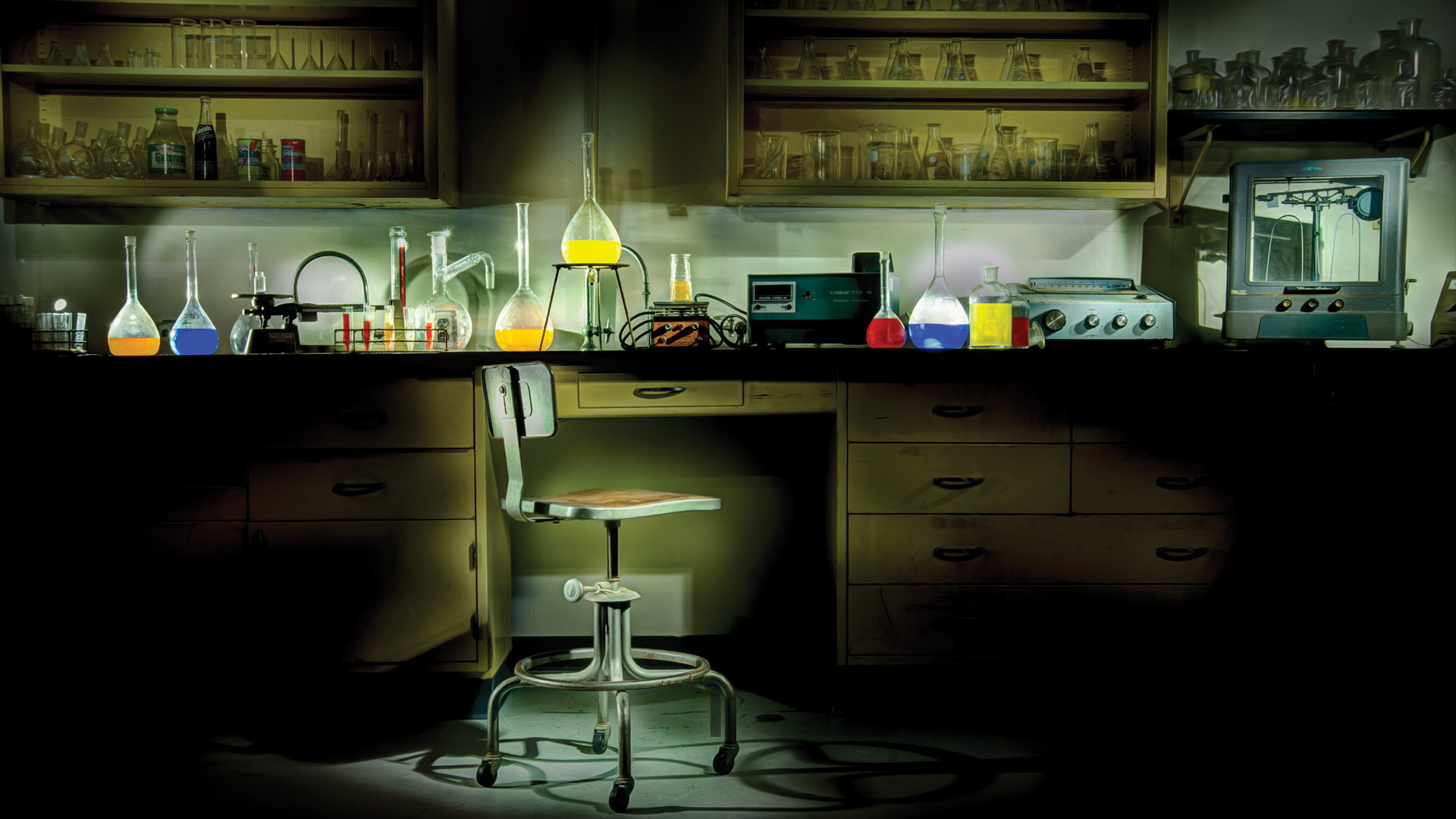

Based on their findings, the team went into the lab and experimented with solutions of salts and sugars designed to replace the chemicals players were losing through their sweat. By all accounts, the first batches of what would become Gatorade were undrinkable, but with the addition of lemon juice at the suggestion by Dr. Cade’s wife, it became palatable.

The first test came on October 1, 1965 when the freshman team played the UF varsity B team in an intra-squad scrimmage. Members of the underdog freshman team were given the experimental concoction, but the varsity B players were not. The B team jumped out to an early lead but the freshman team dominated the second half. The coaches and doctors realized they were on to something.

UF was scheduled to play the 5th ranked LSU Tigers in Gainesville the next day, so the head trainer asked Dr. Cade and his team to have the new drink available on the sidelines for the game.

The researchers worked through the night mixing 25 gallons of the drink for the game. The Gators won 14-7 when LSU wilted in the 102-degree heat during the fourth quarter. The coaches and trainers were now all in on using this drink to their advantage and it became a staple for the Gators the rest of the season.

ESPN once created a list of the top 5 most heartbreaking UF losses in its storied rivalry with Georgia, and among these is the 1966 matchup. The Gators, led by eventual Heisman Trophy winner Steve Spurrier, entered the game unbeaten and needing a victory to clinch at least a share of the school’s first SEC title.

Legend has it that Florida’s supply of Gatorade mysteriously disappeared prior to the game and the Gators’ 10-3 halftime lead turned into a 27-10 Bulldog victory.

As the Gators’ reputation as a second-half team and their use of Gatorade grew, Dr. Cade and his colleagues began pursuing commercial interest in the product.

As the Gators’ reputation as a second-half team and their use of Gatorade grew, Dr. Cade and his colleagues began pursuing commercial interest in the product.

In the spring of 1967, Dana Shires and others paid a visit to Stokely-Van Camp, a company based in Indianapolis that was best known for making baked beans.

Company executives knew the product’s reputation and saw its potential, so Stokely-Van Camp acquired rights to produce and sell the beverage.

Gatorade was on its way to the big-time.

When cereal giant Quaker Oats acquired Stokely-Van Camp in 1983 and put its considerable marketing power behind Gatorade, sales soared like pitchman Michael Jordan’s dunks. In Forbes’ 2012 list of the world’s most valuable brands, Gatorade was ranked number 86. In 2001, PepsiCo acquired Quaker Oats and today annual sales of Gatorade exceed $3 billion.

For UF, the story of Gatorade continues. It is impossible to overstate the impact of Gatorade on the University of Florida. Since 1972, the university has received more than $280 million in royalties from Gatorade, resources that are invested in a wide variety of research.

Gatorade royalties have been instrumental in helping UF build or equip some of its leading research facilities, such as the Research and Academic Center at Lake Nona in Orlando. It has helped to equip laboratories in nanoscale science and nanotechnology, in brain research to address neurological disease and injury, in biotechnology, and in research computing.

But just as in 1965, doing great things is about people. It’s about assembling brilliant people who see an important challenge and dedicate themselves to doing something about it, to making a difference.

Gatorade and other products enable many UF faculty to pursue such challenges.

They are seeking to improve the health and lifestyle of an elderly population that is growing dramatically. They are recognizing the incredible impact of education and environment during early childhood. They are seeking treatments and cures for diabetes, malignant brain tumors and blindness. They are engineering solutions to help buildings withstand hurricane-force winds and helping to tame Big Data for everything from medical records to museum specimens. Many of these research efforts directly benefited from Gatorade royalties. All benefited indirectly.

Since 1965, the University of Florida has evolved from an institution whose impact was mostly local into a university whose research and education is impacting the lives of people locally, nationally and globally. We are seeking solutions to some of the most pressing issues facing our planet.

We are building on a legacy that includes four remarkable men – Robert Cade, Dana Shires, James Free and Alejandro de Quesada – who back in 1965 set out to address a local problem, solved it and helped others, and in the process created a drink known as Gatorade.

Today we look back on an invention made 50 years ago, but more importantly we look forward to what lies ahead.

I have to go now. I need to log in a long run in preparation for my next marathon. I’ve got my charged iPod, my GPS watch, and, of course, a bottle of Gatorade.