Extracts

Breath Sensor Could Ease Disease Tests

By Aaron Hoover

A tiny sensor could provide inexpensive new diagnosis and treatment methods for people suffering from a variety of diseases.

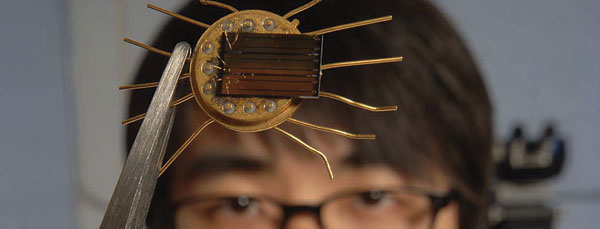

University of Florida engineers have designed and tested versions of the sensor for applications ranging from monitoring diabetics’ glucose levels via their breath to detecting possible indicators of breast cancer in saliva. They say early results are promising — particularly considering that the sensor can be mass produced inexpensively with technology already widely used for making chips in cell phones and other devices.

“This uses known manufacturing technology that is already out there,” said Fan Ren, a professor of chemical engineering and one of a team of engineers collaborating on the project.

The team has published 15 peer-reviewed papers on different versions of the sensor, most recently in the January edition of IEEE Sensors Journal. In that paper, members report integrating the sensor in a wireless system that can detect glucose in exhaled breath, then relay the findings to health-care workers. That makes the sensor one of several non-invasive devices in development to replace the finger prick kits widely used by diabetics.

Tests with the sensor contradict long-held assumptions that glucose levels in the breath are too small for accurate assessment, Ren said. That’s because the sensor uses a semiconductor that amplifies the minute signals to readable levels, he said.

“Instead of poking your finger to get the blood, you can just breathe into it and measure the glucose in the breath condensate,” Ren said.

In the IEEE paper and other published work, the researchers report using the sensor to detect pH or alkalinity levels in the breath, a technique that could help people who suffer from asthma better identify and treat asthma attacks — as well as calibrate the sensitivity of the glucose sensor. The engineers have used other versions to experiment with picking up indicators of breast cancer in saliva, and pathogens in water and other substances.

As with the finger prick standard, tests for pH, breast or cancer indicators typically already exist, but they are often cumbersome, expensive or time-consuming, Ren said. For example, the current technique for measuring pH in a patient’s breath requires the patient to blow into a tube for 20 minutes to collect enough condensate for a measurement.

At 100 microns, or 100 millionths of a meter, the UF sensor is so small that the moisture from one breath is enough to get a pH or glucose concentration reading — in under five seconds, Ren said.

Ren said the sensors work by mating different reactive substances with the semiconductor gallium nitride commonly used in amplifiers in cell phones, power grid transmission equipment and other applications.

If targeting cancer, the substance is an antibody that is sensitive to certain proteins identified as indicative of cancer. If the target is glucose, the reactive molecules are composed of zinc oxide nanorods that bind with glucose enzymes.

Once the reaction happens, “the charge on the semiconductor devices changes, and we can detect that change,” Ren said.

While the sensor is not as acutely sensitive as those that rely on nanotechnology, the manufacturing techniques are already widely available, Ren said. The cost is as little as 20 cents per chip, but goes up considerably when combined with applications to transmit the information wirelessly to computers or cell phones. The entire wireless-chip package might cost around $40, he said, although that cost could be cut in half with mass production.

The team has patented or is in the process of patenting several elements of the technology, and several companies have expressed interest in pursuing the research, Ren said.

“This is an important development in the field of biomedical sensors and a real breakthrough,” said Michael Shur, professor of solid state electronics at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. “Professors Fan Ren and Steve Pearton have made pioneering contributions to materials and device studies of nitrides, and now their work has led to the development of sensors that might improve quality of life for millions of patients.”