About Face

|

| photo by: Gene Bednarek |

By Joseph Kays

In a world consumed by an idealized concept of beauty, a facial disfigurement can be a heavy physical and emotional burden.

Children with cleft lip and palate and other facial disfigurements, and their families, often endure years of painful operations and sometimes even more painful ridicule from classmates, neighbors and even relatives before they can hope to achieve what society considers a ``normal'' face.

But for more than three decades researchers at the University of Florida have been working to ease that pain through a research, education and clinical program that has attracted the attention of peers throughout America and from Brazil to Russia. In 1981, the program became the UF Craniofacial Center, an interdisciplinary group that includes faculty from the colleges of medicine, dentistry and health professions.

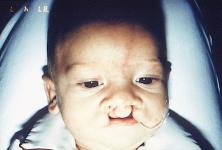

A cleft is the lack of fusion of the upper lip and/or roof of the mouth. It

can range from a slight notch in the lip or palate to a complete opening

through the lip, gum ridge, hard and soft palate.

|

The University of Florida is an integral part of a worldwide effort to better treat disfiguring cleft lip and palate

|

One of the most common birth defects, cleft lip and/or palate affects about one in every 750 newborn babies. An estimated 5,000 Florida families include at least one child with the malformation, with another 350 babies born with the problem annually in the state.

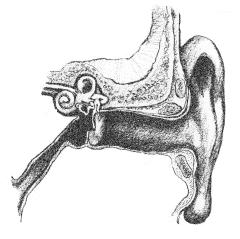

Beyond the obvious aesthetic problems, clefts present a host of physical challenges for a baby, including sucking problems that inhibit effective nursing, eustacian tube dysfunction that leads to frequent ear infections, and speech impediments caused by air escaping through the open palate, missing or improperly aligned teeth, and/or hearing difficulties.

While parents of a child born with a cleft often are shocked, confused and even ashamed or embarrassed, Dr. John Nackashi, medical director of the UF Craniofacial Center, says there is good cause for optimism.

``Parents may have a hard time believing doctors who say their baby will be all right,'' Nackashi says, ``but impressive strides have been made in the treatment of cleft lip and palate in recent years.''

Doctors usually perform surgery to repair cleft lip during a baby's first three months. They generally wait a little longer to repair the palate, until the child is at least six months old, but before he or she begins to speak. The main goals of palatal surgery are to give the child a palate long enough to seal off the nose from the throat and mouth to allow for normal speech and eating and to repair the soft palate so its muscles can help open the eustacian tube to prevent fluid build-up in the middle ear.

No Boundaries

Cleft lip/palate is a defect that knows no political or geographic

boundaries, so in recent years UF researchers have increasingly collaborated

with colleagues in other parts of the world. These collaborations allow the UF

doctors to work in countries that have more centralized treatment centers for

cleft lip and palate, and to compare different methods of surgical repair.

``Parents may have a hard time believing doctors who say their baby will be all right, but impressive strides have been made in the treatment of cleft lip and palate in recent years.'' Dr. John Nackashi

|

One of the most promising collaborations arrived unexpectedly in early 1990 on the desk of Bill Williams, the UF Craniofacial Center's director.

Williams thought there was a typographical error in the letter he received from Dr. Jose Alberta de Souza Freitas, director of the Hospital for Research and Rehabilitation of Cleft Lip and Palate in Bauru, Brazil.

``Their letter said they had 15,000 cases and I figured it was 1,500 cases, which still would have been three times the case- load we had,'' Williams says. ``Turns out there was no mistake. They have 30 times as many patients as we have, with a current caseload of more than 20,000 patients and gaining at a rate of 1,200 new cases each year.''

The hospital, known affectionately as Centrinho (``Little Center''), is situated adjacent to the campus of the University of São Paulo School of Dentistry and is served by a full complement of medical, surgical, dental, psychology and speech-language and hearing specialists. The hospital provides cleft repair and therapy free of charge.

Freitas' proposal that the two institutions develop a joint research program to evaluate the efficacy of cleft lip/palate treatments on large numbers of patients was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the UF researchers, who had all the research tools to conduct large-scale studies, but not nearly enough patients.

``To do effective clinical research, you have to have large numbers of patients. For us to do a large-scale study would have required the nearly impossible coordination of multiple sites all around the country,'' Williams says. ``In Bauru, they have thousands of patients whom they have tracked carefully over many years. Brazil was the solution to our numbers problem.''

William Wharton, the center's director of international program

development, adds: ``In one week of clinic visits at the hospital in

Brazil, the UF staff will see more patients than can be seen in an entire year

in Gainesville. Such a concentration of patients enables the professional staff

to become better and more rapidly familiar with the nature of cleft and its

many associated syndromes.''

One of the most common birth defects, cleft lip and/or palate affects about one in every 750 newborn babies.

|

Marie Ines Pegoraro-Krook, a faculty member of the Department of Phonoaudiology at the University of São Paulo and Williams' counterpart in Brazil, echoes her colleagues' sentiments: ``The number of cases we have and the heterogeneity of our patient base, combined with the scientific expertise of the University of Florida, gives us an opportunity to define better, more advanced methods of treatment for patients with craniofacial disorders.''

Freitas' initial letter led to a series of exchange visits and, ultimately, a formal agreement in February 1991 between the University of São Paulo and UF.

Since then, the two institutions have secured a five-year, $1 million grant from the National Institute for Dental Research to compare the two most common surgical repairs for cleft palate and how they affect speech development.

``There has been little comparative research that has examined either speech or facial growth as an outcome of surgical cleft palate repairs,'' Williams says.

During this study, a team of UF doctors led by Dr. Brent Seagle, the UF center's primary surgeon, and their counterparts in Brazil will try to confirm evidence that a new treatment developed by retired UF surgeon Leonard Furlow in the mid 1980s results in fewer speech problems than the von Langenback surgical repair, a technique doctors have used for more than a century.

``Normal speech is critically important for the normal development of a

child,'' Williams says, ``but surgery is not always effective in

closing the palate completely enough to prevent air from escaping during

speech, so children have difficulty producing speech without the sounds coming

through their noses.''

Another serendipitous discovery has led to a joint study among the UF Craniofacial Center and centers in Russia, Ukraine, Sweden and Brazil.

Otitis media (middle ear disease) is one of the most common healthcare conditions of childhood, affecting millions of children annually. In addition to the pain it causes, the disease can impair hearing, leading to impaired cognitive, language and speech development.

Children with cleft palate are particularly susceptible to the condition because their palatal muscles are unable to assist in opening the eustacian tube, the structure that aerates and drains the middle ear.

Typically, in the United States and most Western countries, doctors use

antibiotics and pressure equalization tubes inserted into the ear drums to

drain the ears with the intent of ensuring the proper development of cognition,

language and speech.

But in a February 1993 visit to the National Pediatric Center in Moscow, UF researchers made an unexpected observation.

A group of 112 Russian children who had received relatively little post-surgical treatment of cleft palate had no higher incidence of otitis media or hearing loss than children who had undergone cleft palate surgery at UF's Shands Hospital and received extensive middle ear treatment with antibiotics and tubes.

``There have been warning signs that we have been overtreating children generally for otitis media, but there haven't been adequate data to prove it,'' Williams says. ``It's very difficult to find children in the United States who haven't been treated for ear infections with antibiotics, so by going to Russia and Ukraine, we will be able to gain additional insight into whether we are overtreating.''

With support from UF's Office of Research, Technology and Graduate

Education, a UF team began working in May 1995 with researchers from the

National Pediatric Center in Moscow. The study will involve the Regional

Stomatological Polyclinic in Krasnodar, Russia; the Maxillofacial Center in

Donetsk, Ukraine; the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden; and the

University of São Paulo, to assess the hearing of 500 children between 5

and 10 years old to determine whether the preliminary findings are

consistent.

| ||||||||||||||||||

Each center will compare 50 children who have had cleft repairs and 50 children with no history of cleft for hearing ability and middle ear function.

``If the children treated at UF show higher learning, language and cognition, then antibiotic treatment may be the appropriate way,'' Williams says. ``Right now, however, treatment is provided on a best-guess basis.''

Initial results will serve as the basis for a National Institutes of Health proposal to conduct further research.

Other international collaborations being planned include an extension of the current NIDR study in Brazil to determine the effect the two surgical procedures have on facial growth and one to study adults with unrepaired clefts at a clinic in Manaus, Brazil, where a large percentage of adults with clefts are surgically treated.

``This study would be unique in the annals of craniofacial research,'' Williams says, ``because no other known center has sufficient adult cases of unrepaired cleft palate to allow statistical analysis.''

The UF team also is considering a cooperative study with geneticists in Ukraine, Russia and Brazil to try to more accurately determine the cause of cleft palate.

``There is a paucity of good answers about what causes cleft palate,'' Williams says. ``But with a large population of patients and associated families to study, we should be able to begin to throw significant light on the hereditary factors of these disorders.''

Of particular interest to researchers is the possibility that radiation fallout from the nuclear accident at Chernobyl has contributed to a recent increase in the frequency of cleft palate in that region of Ukraine. The researchers are pursuing funding for a study through a foundation called The Children of Chernobyl and through the National Institutes of Health.

Human Side Of Cleft

``Not surprisingly, we have found that families who have a child with a craniofacial malformation benefit greatly if they can talk with other parents who have gone through similar experiences,'' Williams says.

Toward that end, the center has worked to develop family networks in counties

throughout Florida and has offered an annual Craniofacial Camp for families who

have a child with a cleft palate who is approaching adolescence.

| ||||

The camp has become so popular that for the past two years the Florida Legislature has appropriated funds for an annual statewide camp, modeled after the UF camp.

At the most recent statewide camp last May, several dozen children and their families participated in a host of activities designed to help children develop coping skills, and to assist families in developing a support network that includes professionals and other families experiencing similar problems.

``The nicest thing about this camp is that no one has to worry about being teased here,'' Williams says. ``They've all been through the same ordeals and they all understand.''

To reach the Florida Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association, call (800) 726-2029. Outside of Florida, call the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association in Pittsburgh, Pa. at (800) 242-5338.

Pegoraro-Krook also lauds the educational opportunities for both UF and University of São Paulo students.

UF and Centrinho have been conducting faculty exchanges for six years. Three years ago, UF began hosting a special two-week program for Brazilian speech therapy students that has been so successful that the number of participants has doubled each year. This year, 15 dental students also are participating in a special two-week course.

William Williams

Director, UF Craniofacial Center, (352) 846-0801, williams@dental.ufl.edu

| An Ambassador for Cleft Treatment | |||

Jeniffer Dutka was already a certified speech pathologist at one of the world's largest centers for cleft lip and palate when she embarked on a mission from her native Brazil that would change her life and her institution's relationship with the world. ``Few professionals outside of Brazil knew about the work we were doing,'' Dutka says of the Hospital for Research and Rehabilitation of Cleft Lip and Palate in Bauru, Brazil. ``We needed guidance in how to fulfill our clinical mission, and to develop research programs that would be published internationally.'' Because she spoke English better than many of her colleagues, Dutka was chosen to approach the UF Craniofacial Center about a joint relationship that would combine the huge patient base at her institution with the strong research component available at UF. That initial visit in early 1990 has resulted in strong ties between the two institutions, and between Dutka and UF Craniofacial Director Bill Williams. ``I know my hope is that Dr. Williams and I have developed a life-long relationship,'' Dutka says. ``He is my mentor.'' For Williams, Dutka is a special kind of graduate student: ``In my 30 years of teaching, Jeniffer is one of those rare students who quickly became a colleague, and now a close personal and family friend.'' Since matriculating in fall 1990, Dutka has earned her master's degree and expects to complete her dissertation and earn her Ph.D. in communications processes and disorders this fall. Dutka's research and her participation in the joint UF-Brazil program was considered so valuable that she won a highly competitive national scholarship to have her doctoral research funded by the Brazilian government. Dutka's dissertation focuses on perceptual and instrumental measures of speech nasality and should provide speech pathologists in the United States and Brazil with a tool to organize and quantify speech outcomes after cleft palate surgery. Children with a cleft palate often develop a very nasal tone to their speech because air and sound inappropriately escape through their nose. Dutka's dissertation focuses on adapting a device called a nasometer so different researchers at different institutions measure nasality using the same standard. ``What might sound like a 10, or severe nasality, to the average person might only be perceived as a four to a speech pathologist,'' says Williams, her major adviser. ``With this device, a six will be a six, no matter who performs the test.'' |