An Once of Prevention, A Pound of Cure

|

UF researchers race to unlock the mysteries of diabetes

by Melanie Fridl Ross

Cure. Most medical researchers are reluctant to use the word, even though it is their ultimate goal. No sense giving patients false hope, they reason. As is so often the case with science, progress usually comes in microscopic steps.

But as they toil in laboratories throughout the University of Florida Health Science Center, scientists studying insulin-dependent diabetes are slowly beginning to whisper the word. Someday they hope to shout it from the rooftops.

If anyone would love a cure, it's Cynthia Bonfiglio. The 43-year-old

Orlando resident is all too familiar with the merciless disease, which

most often strikes the young, shortening a person's lifespan by as

much as a third and leading to a strict diet and exercise regimen and

a daily ritual of injections and blood tests.

|

photo by Russ Lante

More than 750,000 Americans battle insulin-dependent diabetes and one in seven health-care dollars goes to treating the disease |

Her mother-in-law had been diabetic for years, so when Cynthia Bonfiglio's oldest daughter, Layla, began to complain of unquenchable thirst seven years ago, drinking gallons of liquid a day, she knew the telltale signs.

The months after 13-year-old Layla was diagnosed with diabetes were a real ``rollercoaster ride,'' Bonfiglio recalls.

``She was in a state of denial for a time. She'd take foods she shouldn't be eating and binge on them, then take extra insulin to bring her blood sugar down.''

Layla, who gives herself daily insulin injections, attended UF's diabetes camp the year after her diagnosis. That's when Bonfiglio got more startling news: through routine blood testing of campers' relatives, UF physicians told her she herself had tested positive for a key autoantibody that signals the body's destructive autoimmune attack leading to diabetes.

``I was devastated,'' Bonfiglio says. ``I have absolutely no history of diabetes on my side of the family.''

Based on promising research at UF, doctors placed her on prophylactic insulin injections to help prevent or delay the disease. So far, it's working.

Meanwhile, her younger daughter Jessica, now 13, tested positive for a different diabetes marker four years ago, and is closely monitored at the federally funded Clinical Research Center at Shands at UF.

UF researchers say Bonfiglio and her daughters exemplify their two-pronged approach toward battling diabetes.

``In terms of finding a cure, we need advances on two fronts,'' says pathologist Mark Atkinson, director of UF's Center for Immunology and Transplantation. ``We need to find a way for individuals who already have the disease to stop taking insulin injections and avoid the complications associated with diabetes, and we have to discover a method of preventing the disease in those we identify at increased risk for getting it.''

For nearly two decades, UF diabetes researchers have set their sites on three main questions: Can you predict diabetes? Can you find a way to prevent diabetes? What causes diabetes?

``I feel we've made great inroads on the first two,'' Atkinson says. ``But the third one still remains a huge black box.''

UF pediatric endocrinologist Desmond Schatz says diabetes research today reminds him of cancer research 20 years ago, when only 5 to 10 percent of patients who were treated survived. Today, such patients have a host of options, from radiation therapy to chemotherapy to bone marrow transplantation, and the cure rate for some cancers is 80 percent.

Prevention based on prediction is a much-heralded battle cry. UF research spearheaded by Dr. Noel Maclaren more than 20 years ago led to the first reliable ways of screening individuals and determining their risk of developing diabetes. As scientists were able to more accurately forecast who would get the disease, they turned their attention toward possible ways of preventing it.

A massive effort to screen at least 60,000 people at risk for diabetes is a key part of the first nationwide study that aims to halt or delay the disease through daily doses of insulin --- either oral or injectable.

Prediction efforts continue to be refined. Already, UF researchers are contemplating a newborn screening project that would assign degrees of risk to babies tested at birth for the known genes for diabetes. And the diabetes research team recently submitted a $5.6 million project proposal to the National Institutes of Health to study a combination of genetic screening and white blood cell responses as a way of more economically and accurately predicting diabetes.

Cellular Suicide

Insulin-dependent or ''type 1'' diabetes occurs when white

blood cells vital to the body's defenses against infectious diseases

launch a self-directed or ``autoimmune'' attack on insulin-producing

beta cells in the pancreas. The insulin these beta cells produce regulates how

the body uses and stores sugar and other food nutrients for energy.

|

photo by Russ Lante

|

Research has shown that the pancreas is a resilient organ and more than half of its insulin-producing beta cells must be irreversibly destroyed before an individual develops symptoms of the disease --- frequent urination and increased fluid and food consumption. While these symptoms appear abruptly, the disease process itself takes months or even years to occur.

``Insulin-dependent diabetes was once viewed as a rapidly developing illness causing symptoms similar to those resulting from an acute viral infection,'' Atkinson says. ``But UF researchers have found that the disease actually results from a chronic autoimmune process that 'smolders' years before symptoms appear.''

That quirk could be diabetes' Achilles' heel: The long period prior to the onset of symptoms provides an opportunity for interventions aimed at preventing the disease's development.

More than 750,000 Americans battle insulin-dependent diabetes. Each year, at least 35,000 people are diagnosed with the disease in the United States. Many suffer major side effects, including damage to blood vessels, which can lead to heart disease, stroke, blindness, kidney failure and poor circulation to the lower limbs.

Type 2 or non-insulin-dependent diabetes differs from its type 1 cousin in that it usually occurs in overweight individuals who typically fail to exercise regularly. These people develop a resistance to insulin, leading to symptoms of the disease. They, too, have a strong genetic predisposition to the disease, and account for 90 percent of the nation's estimated 7 million diabetics. Another 7 million Americans are actually thought to have the disease but don't know it. Many can control the disease through weight loss and exercise and do not depend on insulin injections.

But for the 10 percent of diabetics who are insulin-dependent, diabetes often requires daily shots, a careful eye to diet and rigorous exercise schedules in order to maintain normal blood sugar levels, which must be checked several times a day.

Every year, diabetes accounts for 20,000 new cases of end-stage kidney failure as well as 15,000 cases of blindness a year and 50,000 amputations, according to the National Institutes of Health.

The disease takes an economic toll, as well. Total diabetes health-care costs in this country exceed $120 billion, and insulin-dependent diabetes accounts for a disproportionate share of those costs. One in seven health-care dollars goes to diabetes.

``That's part of the impetus for our research,'' Schatz says. In addition to millions in funding from the NIH, UF diabetes researchers this past year received seven grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation, more than any other university in the nation.

A Medical Mystery

diagram from Blausen Medical Communications |

Just what causes type 1 diabetes is not yet clear. During the past five years or so, the scientific community has focused on two favored candidates: a virus or environmental influences such as diet.

Atkinson was among a group of UF researchers who implicated heightened immunity stemming from infection by a polio-related virus known as Coxsackie --- in conjunction with genetic susceptibility --- as a possible cause.

More recently, both Atkinson and Schatz --- writing in the international journals Lancet and the Journal of the American Medical Association, respectively --- have debunked the idea that consumption of cow's milk or milk-based infant formula plays a role in the disease process.

Doctors do know one thing: If you have a family history of diabetes, you are at increased risk for the disease. However, of the people who surface in their offices, about 85 percent have no family history of diabetes.

Minus a family history of type 1 diabetes, an individual has about a 1 in 300 chance of getting it. With a family history, it rises to 1 in 20.

Type 1 diabetes also is becoming more common. Some estimate its incidence is rising at a rate of 6 percent a year in the U.S. population --- independent of improved diagnostic tests --- and most of these people do not have a family history of the disease.

UF researchers are making headway solving a challenging genetic puzzle that could help crack the conundrum: unearthing the small bits of DNA that make some people prone to diabetes.

People with diabetes may have one or more of what are known as ``susceptibility genes'' --- genes that do not directly cause the disorder but instead appear to render a person vulnerable to environmental forces that trigger the debilitating strike on beta cells. Though it is possible to have many of the genes and never develop diabetes, the greater the number, the higher the likelihood of getting it. Ten or more may play a role.

Locating the genes is more than an academic exercise. The knowledge will aid researchers in understanding how and why diabetes develops.

A team of scientists led by UF's Jin-Xiong She has confirmed the location of three such genes.

The geneticist studied DNA samples from hundreds of families worldwide who have two siblings with insulin-dependent diabetes. Armed with maps depicting the location of known genes and other markers on DNA strands, She was able to identify patterns of inheritance and mathematically determine the chromosome regions where the genes associated with diabetes are located. Additional work is needed to pinpoint their precise position.

Further complicating matters, other genes appear to protect people from diabetes --- even if they have inherited the susceptibility genes.

Two Decades Of Discovery

|

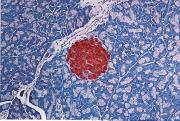

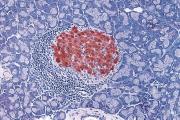

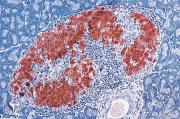

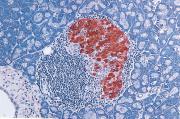

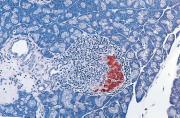

In this series of photographs depicting the process

leading to insulin-dependent diabetes, white blood cells (stained blue)

surround an insulin-producing beta cell (stained red) and begin attacking,

eventually destroying their target.

|

- Identification of more than five genes associated with a predisposition to the disease, the most important occuring on chromosome 6.

- Discovery that 1 in 4 people produce an antigen on their white blood cells that prohibits development of the disease.

- Discovery of marked differences in a person's risk for diabetes according to age, antibody status and family relationship with a diabetic.

- Discovery of an enzyme called glutamate decarboxylase, or GAD, which, when attacked by the immune system, may be the first in a cascade of events leading to the eventual onset of diabetic symptoms.

- Development of a blood test that detects GAD and diabetes-related disease-fighting proteins known as antibodies --- which signal the autoimmune attack is under way --- long before symptoms appear.

UF researchers also were among the first to identify islet cell autoantibodies (ICA). These autoantibodies are present in 3 to 4 percent of relatives with type 1 diabetes and 10 to 15 percent of newly diagnosed adults with diabetes. They react to at least three proteins within islet cells, including GAD, all of which can be detected separately and alert physicians to the destruction of beta cells.

An Ounce Of Prevention

Noel Maclaren and a group of dedicated UF researchers are pioneers in the work that led to the nation's first large-scale prevention study. Their findings have led to an improved understanding of the natural history of diabetes. Researchers now have a good idea who will develop the disease.

In the mid-1980s, Maclaren and Atkinson discovered that giving mice bred to develop diabetes daily insulin injections before the onset of the disease actually prevented it. One theory to come from these studies was that pancreatic beta cells would not have to produce as much insulin and thus would be less of a target for the immune system. The process is called ``beta cell rest.''

UF researchers also found that feeding insulin to those same mice also delays the disease significantly.

In the 1980s, UF's Dr. Janet Silverstein and colleagues showed some success in preventing or delaying the onset of diabetes by giving at-risk individuals the immunosuppressant drug Imuran, commonly used to prevent organ rejection in transplant recipients. But the drug can cause kidney damage and also made participants more prone to infection.

These studies paved the way for the current quest: Can diabetes be prevented or delayed in humans through daily oral capsules or low-dose injections of insulin?

Researchers theorize that oral insulin may work by alerting the body it is about to encounter something beneficial, like food, thereby suppressing the harmful immune response.

Nine other medical centers nationwide and a network of 300 satellites and affiliates are participating in the $31million diabetes prevention trial, known as DPT-1. The national trial is funded by the NIH, the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation, the American Diabetes Foundation and Eli Lilly and Company.

UF is now the national screening site for blood samples amassed across the nation. Nearly 45,000 samples have been shipped to Gainesville, where they are analyzed for the presence of that biochemical ``crystal ball,'' islet cell autoantibodies.

``It's due to our efforts that DPT-1 was in fact launched,'' says

Schatz, center director for UF's arm of the study. ``We have a very

successful team that enabled us to predict diabetes, which enabled the

development of a prevention trial.''

|

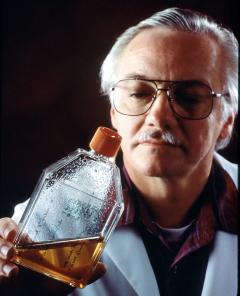

photo by Russ Lante

UF immunologist Dr. Ammon Peck holds a flask of islet-like structures that he used to successfully produce insulin and reverse diabetes in mice like the one on the right in the photograph on page 23. |

For the first time, an oral insulin capsule is being tested in hundreds of people in an attempt to prevent or delay the onset of insulin-dependent diabetes.

Hundreds of study participants will have to be tracked for years before physicians know whether the capsule --- taken every day before breakfast --- is effective. But for diabetics who must endure daily insulin injections, not to mention the disease's troubling side effects, the studies are an encouraging first step.

Researchers determine whether study participants should receive insulin capsules or daily insulin injections based on screening tests that determine their risk of developing diabetes within the next five years.

If tests indicate participants have a 25- to 50-percent risk, they are assigned to the oral insulin part of the study. If it is determined they have a greater than 50-percent risk, they are assigned to receive daily insulin injections in an attempt to hold the disease at bay.

More than 60,000 Americans will be screened to find 830 patients, ages 3 to 45, who will be followed for five years.

In addition, Eli Lilly is sponsoring a study of 300 patients, ages 5 to 60,

who are newly diagnosed with diabetes but have not been treated with insulin

injections for more than six weeks. The aim of this study is to determine

whether oral insulin can preserve whatever pancreatic beta cell function is

remaining, to enable better control of the disease. More than 3,000 prospective

participants will be screened. Those who are selected receive oral insulin or a

placebo. Researchers will focus on both adults and children in this study.

Of Mice And Men

|

photo by Russ Lante

|

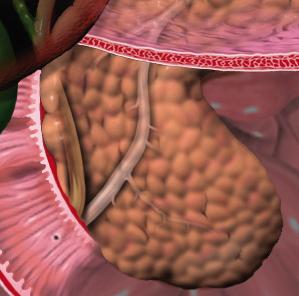

While other researchers focus on prevention, UF's Ammon Peck attacks the diabetes problem from another angle. His team is busy designing an alternate form of therapy for individuals who already have the disease. Researchers in Peck's lab have successfully grown insulin-producing tissue from individual beta cells harvested from prediabetic mice, restoring their ability to regulate insulin secretion and eliminating the need for insulin injections.

His studies showed new pancreatic tissue formed just outside the kidney at the site where the lab-grown cells were surgically implanted. Within this pseudo-pancreas, new islet-like structures developed with a normal blood vessel network, suggesting the tissue was functioning.

Surprisingly, the lab-grown tissue appears to be resistant to the self-attacking forces that cause diabetes.

``Diabetes is a devastating disease,'' Peck says. ``We have found the islet implants tend to reverse that devastation and allow mice to come off insulin.''

Peck estimates researchers are at least five years away from taking the technology --- which has been licensed to Ixion Biotechnology Inc. for further development --- from the lab to clinical studies. His research has been supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International and Ixion Biotechnology, which has a research facility at UF's Sid Martin Biotechnology Development Institute.

A Team Approach

Members of the UF diabetes research team represent many departments within UF's Health Science Center, from pediatrics to pathology. They collaborate with the hope that today's studies could yield tomorrow's answers. Other projects under way include:

- In the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial, Silverstein and UF psychologist Suzanne Johnson are looking at factors that lead to better control and therefore fewer complications in patients with diabetes.

- UF dental researcher Michael Humphreys-Beher and Peck are collaborating on the study of Sjogren's syndrome, an autoimmune disease people with diabetes often develop. Sjogren's causes a physiological breakdown of the exocrine glands, leading to dry eyes and dry mouth. A grant from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation is enabling them to study the disease's underlying mechanisms in mice.

- Dr. Maria Grant is studying retinopathy, a leading cause of blindness in young adults and a complication that affects 80 percent of individuals who have been diabetic for more than a decade. Retinopathy results when blood vessels at the back of the eye become blocked and multiply rapidly. Through a four-year grant from the National Eye Institute, Grant is studying compounds that prevent or reverse retinopathy, with the hope of eliminating the need for laser therapy, which can destroy healthy eye tissue.

- Atkinson is working to better define which proteins are targeted by white blood cells mounting an autoimmune attack, with the goal of using those responses to better predict who will develop diabetes. Thanks to a five-year, $1.4 million NIH grant, he and Dr. Michael Clare-Salzler also are tracking people taking prophylactic insulin to develop lab tests that indicate how that therapy is working.

- Dr. Bill Winter, through funding from the NIH, is studying the disease process, the genes involved and possible interventional strategies in a unique form of diabetes, type 1.5, that is prevalent in African Americans.

- Clare-Salzler is looking at the interaction of macrophages (another kind of

white blood cells that also are called scavenger cells) with genes and the rest

of the immune system to enhance understanding of the disease process leading to

diabetes.

He is examining the role of excessive production of prostaglandin synthase II, an enzyme that may interfere with the immune system's ability to tolerate important body proteins. A breakdown of tolerance is at the root of autoimmune diseases.

- Molecular geneticist Ward Wakeland is working to identify diabetes-causing genes in mice.

``Diabetes is a pretty horrible disease,'' Atkinson says. ``We truly have one of the best diabetes research programs in the country here at UF. We have the resources to find a way to predict the disease, to find out what causes it and to truly find ways to prevent it.''

Bonfiglio hopes for nothing less.

``I'd love to think that maybe one day they'll be able to prevent diabetes from even beginning, or find improved ways of helping my oldest daughter get through it. She certainly did struggle and still does, I'm sure.''

Mark A. Atkinson

Director, UF Center for Immunology and Transplantation

(352) 392-0048,

atkinma@nervm.nerdc.ufl.edu

Desmond A. Schatz

Professor, Department of Pediatrics

(352) 392-0330,

schatz@nervm.nerdc.ufl.edu

Ammon B. Peck

Professor, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

(352) 392-5629,

peck.pathology@mail.health.ufl.edu