Deciphering Drug Design

Raymond Bergeron describes his discoveries in how cells read information carried by polyamine analogues as finding a ``molecular Rosetta Stone,'' comparing them to the key to Egyptian hieroglyphics.The comparison is apt, since the techniques developed over the course of two decades of research by Bergeron, a graduate research professor of medicinal chemistry at the University of Florida's College of Pharmacy, works for a wide variety of drugs on an equally diverse variety of illnesses.

That's also what makes the technology so attractive to SunPharm Corporation. The Jacksonville-based pharmaceutical start-up company obtained rights to market Bergeron's inventions from the University of Florida Research Foundation Inc. in 1991 and currently has 13 potential products in various stages of research or development.

Bergeron's approach is deceptively simple. Polyamines are present in all human cells, and they are essential to cell growth and proliferation. The polyamine analogues Bergeron has developed gain entry to the cell because of their similarity to natural polyamines.

But once inside the cell, the analogues substitute themselves for the naturally occurring polyamines, but do not perform the functions required for cell growth and proliferation. And, they cause the naturally occurring polyamines to leave the cell also.

This has major implications if the cells being targeted are cancerous, because cancer cells have higher concentrations of and rely more on polyamines than normal cells. If their supply of polyamines is shut off, their uncontrolled growth can be stopped.

``When the polyamine-inhibiting drug comes into the cell, it shuts down production of polyamines, and when this natural synthesis is halted, the affected cell dies,'' says Bergeron, whose research over the years has been supported by more than $10 million from the National Cancer Institute.

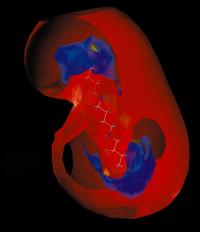

|

| Dr. Raymond Bergeron, graduate research professor of medicinal chemistry at UF (right), has spent more than two decades unlocking the pharmaceutical mysteries of polyamine analogues like the one in this computer-generated image. |

|

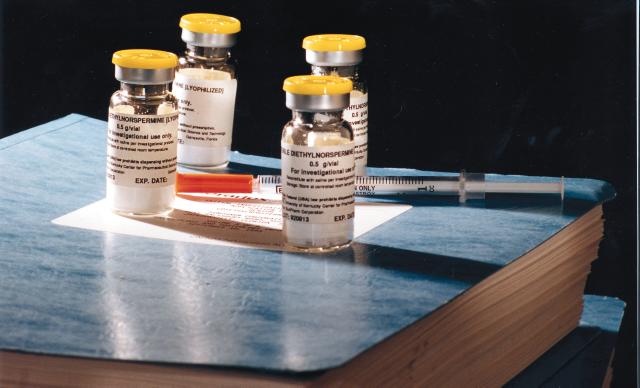

Of the dozens of compounds synthesized in Bergeron's laboratory during the past decade, Diethylnorspermine, or DENSPM, has shown the greatest promise against cancer.

Ninety-two patients whose cancers failed to respond to standard therapies participated in the Phase I clinical study of DENSPM at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, N.Y., Johns Hopkins Oncology Center in Baltimore, Md., and at UF. Preliminary favorable responses have been observed in patients with pancreatic cancer, melanoma and lung cancer.

After completing its Phase I testing of DENSPM in December, SunPharm turned over responsibility for additional tests to Warner-Lambert Co., the New Jersey-based pharmaceutical giant with whom SunPharm has developed a licensing relationship. As part of the agreement, Warner-Lambert paid SunPharm a $1 million ``milestone'' payment.

Another promising drug being developed by Bergeron and SunPharm is diethylhomospermine, or DEHOP. While DEHOP was originally developed as another cancer treatment, Bergeron and his colleagues decided to try to employ a side effect of the drug to treat a different insidious disease.

An estimated 50 percent of all AIDS patients suffer from chronic diarrhea at some point during their illness, causing them to lose weight and become more susceptible to life-threatening infections. A 1994 study by the Stanford University School of Medicine found that the annual charge to patients with AIDS was 50 percent higher for patients with diarrhea than for patients without such symptoms. Patients with diarrhea also suffered more significant work loss and required a greater need for assistance at home.

Beginning in early 1994, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration allowed UF to conduct human clinical trials of DEHOP as a possible treatment for chronic diarrhea in AIDS patients. The drug significantly reduced the incidence of diarrhea in five AIDS patients for whom treatments with other antidiarrheal medications had been unsuccessful. DEHOP is currently in Phase II clinical trials for AIDS-related diarrhea and in Phase I clinical trials for cancer.

Bergeron and SunPharm also are experimenting with DENSPM and DEHOP as a possible treatment for psoriasis, since patients with psoriasis have increased polyamine levels. Clinical trials on the drugs for psoriasis are expected to begin this spring at UF.

In addition to the DENSPM and DEHOP research, Bergeron also has a $3 million grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute to test new oral iron-binding (chelator) drugs for iron overload diseases.

Desferrioxamine (DFO) has been used for more than 30 years to treat patients with iron overload caused by congenital defects or as a consequence of repeated blood transfusions.

Until now, however, the most effective treatment for many patients has been to connect themselves to a tiny pump for six to eight hours of through-the-skin infusions because DFO is inefficient and has a short effective duration in the body.

Bergeron, who is co-editor of the textbook The Development of Iron Chelators for Clinical Use, has isolated fragments of the DFO molecule that play a leading role in binding iron and linked them to new chemical carriers that will work when administered orally.

SunPharm, which signed a license agreement with the UF Research Foundation in 1995 for Bergeron's DFO process, has contracted with the Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry for commercial scale up of DFO.

All of this is good news for SunPharm, a company founded in 1991 by a Chicago-based venture capitalist named Stefan Borg after he read about Bergeron's research in a university brochure and arranged to meet the researcher.

Since then Borg, as president and chief executive officer, has operated a ``virtual'' company with a staff of just five people. Most of the company's needs are subcontracted out --- a French firm manufactures the compounds being developed, a Maryland company handles packaging and sterilization and a New Jersey firm helps coordinate the clinical trials.

Most of SunPharm's capital goes to funding Bergeron's research. So far, SunPharm has paid more than $3 million in research grants to the university, and, in exchange for receiving exclusive rights to Bergeron's compounds, gave the UF Research Foundation 342,760 shares of stock when it went public in January 1995. The shares were trading at about $4.50 in mid March.