Before the advent of microsurgery in the mid-1960s,

neurosurgeons relied on anatomical drawings little changed from the time

of Leonardo daVinci to guide them through a part of the body where even

the slightest misstep can result in death or devastating debilitation for

the patient.

Before the advent of microsurgery in the mid-1960s,

neurosurgeons relied on anatomical drawings little changed from the time

of Leonardo daVinci to guide them through a part of the body where even

the slightest misstep can result in death or devastating debilitation for

the patient.

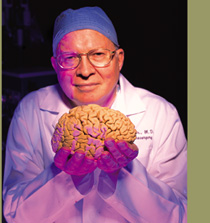

Into this environment came Albert Rhoton

Jr., a young man only a few years removed from a rustic cabin and two-room

schoolhouse in rural eastern Kentucky. Rhoton quickly realized the microscope’s

potential, not only to revolutionize surgery itself but to take brain anatomy

to a new level of detail.

For the first time, the surgical microscope

enabled anatomists to map the brain’s interior landscape using more

than the naked eye. Magnification brought into focus previously invisible

blood vessels branching off and draining from cerebral arteries and previously

unknown connections among vital centers of the brain.

"Knowledge of brain anatomy as studied

under magnification remains the most crucial aspect of the vast refinements

I’ve witnessed in neurosurgical practice,” says Rhoton. “As

surgeons, we need to determine the most gentle and least traumatic, tissue-preserving

approach we can take to reach a specific site to perform corrective surgery,

and anatomical studies through the microscope have helped us do that.”

Now in the 36th year of an illustrious career, Rhoton is regarded by brain

surgeons the world over as the father of microscopic neurosurgery.

Last fall, in recognition of his work, a textbook-sized collection of Rhoton’s

updated papers and illustrations on the brain’s posterior cranial fossa

region was published as part of the international journal Neurosurgery.

The unique “millennium supplement” was designed to serve as a

guide to surgeons operating within this critical region of the brain, containing

nerves that help to control such vital functions as breathing, blood pressure,

balance, consciousness, hearing and vision.

“Anatomy to the surgeon is like the sun for our planet; it gives us

the life-sustaining knowledge to traverse the intricate pathways throughout

the brain,” Arizona neurosurgeon Robert Spetzler wrote in a preface

to the Neurosurgery supplement. “No single neuroanatomist can lay greater

claim to expanding this knowledge for neurosurgeons than Dr. Albert L. Rhoton

Jr.”

With typical humility, Rhoton expresses amazement at a career track that

has taken him from a disadvantaged childhood that began with a midwife assisting

his birth in exchange for a sack of corn to a position as one of the world’s

preeminent neurosurgeons.

Rhoton continues to view the mystery and wonder of the brain with awe. He

also conducts his work with a sense of gratitude for the opportunity to

care for patients, train future surgeons and advance knowledge in what he

calls medicine’s “greatest unexplored frontier.”

“Dr. Rhoton’s gentle, kind and humble manner made every patient,

no matter how anxious or scared, feel so much better, if only for having

met him,” writes Michael F. Kaschke, general manager of the medical

division of microscope manufacturer Carl Zeiss, Inc. which sponsored the

special Neurosurgery issue.

Rhoton

originally planned to become a chemist but found chemistry lacking the human

element he craved and switched to social work. For a while, he also considered

missionary service, but then — after viewing brain surgery on an animal

in a physiology laboratory at Ohio State University — he found his

calling. Today, the tall, imposing man with incongruously large hands for

a brain surgeon says his career is “stimulating and gratifying beyond

my wildest imagination.”

Rhoton

originally planned to become a chemist but found chemistry lacking the human

element he craved and switched to social work. For a while, he also considered

missionary service, but then — after viewing brain surgery on an animal

in a physiology laboratory at Ohio State University — he found his

calling. Today, the tall, imposing man with incongruously large hands for

a brain surgeon says his career is “stimulating and gratifying beyond

my wildest imagination.”

In his soft, Southern drawl, Rhoton speaks eloquently of the human brain’s

“amazing ability to see, feel and experience emotion and comprehend

phenomena as vast as the universe more than a billion light-years across,

and to conceptualize a microscopic world out of reach of our senses.”

And he speaks practically of the fact that the brain is the most frequent

site of crippling and incurable diseases, making neurosurgery a field in

which the stakes are high in terms of human lives.

In addition to honing his own skills, Rhoton has always sought to share

his knowledge with others. Shortly after joining UF’s medical faculty

in July 1972, he set this goal: “I’d like to reach a point of

time in which every second of every day a patient somewhere in the world

benefits from microneurosurgical techniques taught at the University of

Florida.”

Today, that dream seems close to reality.

Michael L.J. Apuzzo, editor of Neurosurgery, says: “No individual who

would call themselves a neurosurgeon can afford to be unfamiliar with Dr.

Rhoton’s highly essential contributions to our field.”

Neurosurgeons everywhere refer to the refined brain maps Rhoton has drafted

with the help of medical illustrators Robin Barry and David Peace, and many

surgeons routinely use the miniaturized instruments Rhoton has designed

for operating on minute blood vessels. More than 1,000 surgeons have attended

Rhoton’s hands-on microsurgical training courses at UF, and many more

have heard his lectures or attended his workshops at medical schools across

the nation and in two dozen foreign countries.

“Every neurosurgeon in the world knows and appreciates Dr. Rhoton as

a master of surgical anatomy,” wrote French neurosurgeon Dr. Bernard

George in another preface to the Neurosurgery supplement. “Personally,

I think that the incredible quality of these pictures reflects the quality

of the man himself.”

Better brain imaging — via the surgical microscope and the newer scanning

techniques of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

— has resulted in immense strides in neurosurgical precision and accuracy

during the prime of Rhoton’s career. And, as world leaders in neurosurgery

have said in many forums, Rhoton stands out among those who have brought

precision and safety to operations that were life-threatening two decades

ago. To cite a few examples:

On the basis of new insights into brain anatomy, Rhoton mapped a more precise

surgical procedure and designed instruments for clipping cerebral aneurysms,

bubble-like sacs on arteries in the brain. Refinements in this procedure

have spared the lives of many people with this serious blood vessel disorder.

Rhoton developed a new surgical approach — entering through a nostril

— to remove tumors on the pituitary gland. His improved approach shortens

surgical time and hospital stays, and reduces the amount of pain experienced

by most patients.

Rhoton has contributed immensely to the development of techniques for removing

acoustic neuromas, tumors on the nerve of hearing, without damaging the

patient’s hearing. Rhoton and colleagues conducted one of the most

comprehensive studies ever of this region.

Rhoton has discovered and developed new and safer surgical approaches to

tumors located in the fluid-filled spaces (ventricles) at the center of

the brain.

“Today, we’re on the frontier of being able to transplant certain

brain cells and tissues to help eliminate symptoms of Parkinson’s disease

and to help restore at least a limited degree of limb function in patients

with severe spinal cord injury,” Rhoton says. “So many things

have been unraveled, yet there is so much more to learn.”

When considering the most rewarding aspects of his career, Rhoton focuses

on the opportunity to care for patients who come to him in deep anxiety

about a frightening diagnosis. The outcomes are not always positive, but

many patients are cured and, in almost all of them, the healing is more

than physical.

One patient, a University of Florida professor who had become depressed

and discouraged with life, found out he had a brain tumor, which in a series

of tests appeared to be malignant. Results of the tests increased his sense

of despair because the tumor involved the speech and writing centers of

his brain so essential to his work.

Rhoton was consulted to perform the necessary surgery and, much to everyone’s

surprise, the tumor proved to be benign, allowing full recovery of brain

function.

The patient later told Rhoton that through the process of living for many

days thinking “it was all over” and then having the threat removed,

his entire perception of the value of life and his enthusiasm for his teaching

and writing were improved. After his recovery, the professor finished a

new textbook and dedicated it to the surgeon.

Another patient who stands out in Rhoton’s memory is Sallye Anderson,

who was diagnosed with an inoperable malignant brain-stem tumor after undergoing

exploratory surgery in Atlanta. Her path to Rhoton’s office was paved

by her perceptive and persistent father, who beseeched Rhoton to see his

daughter. Rhoton found, through a variety of imaging tests, a very different

problem — a large, but benign, tumor called an acoustic neuroma that

he surgically excised.

Grateful for life and for the surgeon who helped her through dark hours

of fear, Anderson moved on with her busy life, taking on new challenges.

She raised funds for a professorship in UF’s neurosurgery department,

then joined and later became president of the Acoustic Neuroma Association.

Rhoton’s passion for improving patient care is a driving force behind

his latest challenge — to help make a clinical addition to UF’s

McKnight Brain Institute a reality. A multistory building situated between

the east end of the Shands at UF medical center and the south side of the

McKnight Brain Institute would include a Neuro-Clinical Research Center

with a research operating room and laboratory complex as well as an acute

care unit, a brain electrical/magnetic signal monitoring lab, a cognitive

research facility and an outpatient care unit.

Perhaps the greatest legacy to Rhoton’s work occurred last year when,

in celebration of 35 years in practice, hundreds of former students, colleagues

and UF staff surprised him with $2 million worth of contributions to establish

the Albert Rhoton M.D. Chairman’s Professorship in Neurosurgery. With

state matching funds, the gifts created a $4 million endowment.

Albert L Rhoton

Professor, Department of Neurosurgery

(352) 392-4331

rhoton@neurosurgery.ufl.edu

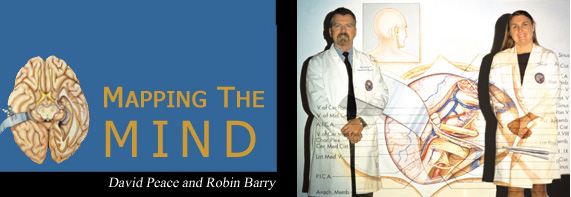

If Dr. Albert Rhoton is the foremost explorer of

human brain anatomy, then David Peace and Robin Barry are the cartographers.

For much of Rhoton’s career, Peace and Barry have been at his shoulder,

in the laboratory and the operating room, shooting pictures, making sketches

and taking notes. Back at their drawing tables and computer workstations,

they’ve taken that information and used it to draw medical illustrations

that have gained them worldwide recognition among neurosurgeons and researchers.

Peace, in his 21st year with the UF faculty, was inspired as a child by

the natural science illustrations at the Smithsonian Institute, which he

visited frequently while growing up in Washington, D.C. He dreamed of drawing

fish, reptiles, frogs and other animals for the Smithsonian, but midway

through graduate studies in medical and biological illustration at the Medical

College of Georgia in Augusta, he became interested in human anatomy and

surgery.

Barry, in her 19th year at UF, graduated with honors from Yale and earned

her Master’s of Art degree through the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine’s

renowned medical illustration program. It was there that she became fascinated

with the brain while observing surgery.

“Before you know much about the human brain, you think about it as

a gelatinous mass,” Barry says. “Then, the more you delve into

it, the more you realize how much you don’t know. And gradually you

realize it’s a never-ending odyssey of learning.”

Peace says the question he hears most often from people curious about his

profession is “Why do they need medical illustrators when you have

cameras?”

He responds with a list of things that can be done by skilled medical illustrators

that can’t be done with cameras — like erasing blood and other

elements in the surgical field that obscure the anatomy of a certain brain

region.

“We can give a three-dimensional appearance to a lot of our illustrations,

and draw in something that is invisible to the camera’s eye —

like a beam of radiation. We can go places conceptually that a camera cannot

go,” he adds.

New computer technology also gives illustrators unprecedented capabilities

to quickly enhance pencil sketches and photos with color, highlights and

complementary backgrounds, and remove distracting elements, Peace says.

Both Barry and Peace have embraced computers to achieve their artistic goals

more quickly and effectively. Barry says much of the photo/illustration

refinements she used to do by hand with paint brushes, air brushes and colored

pencils are now done in sophisticated illustration software.

Her latest challenge involves using software that merges matched pairs of

color slides into a single image that, when projected and viewed through

stereo glasses, appears three-dimensional. The technique, used in several

popular magazines to lend drama to pictures, has a more serious purpose

in neurosurgery — to add visual depth to images of brain structures

to be operated on.

Peace also has ventured into the computer world as designer/manager of the

World Wide Web site for UF’s Department of Neurosurgery (www.neurosurgery.ufl.edu).

Barry and Peace also say the chance to meet and work with leading neurosurgeons

from around the world who come to UF for advanced training is a great career

bonus.

“Some of the foreign surgeons have told me they have kept the reprints

(of my illustrations) in the operating room while performing surgery,”

said Peace. “That is especially gratifying.”