A few years before

his death in 1997, William Maples pondered the fate of the University of Florida

laboratory he had built over the course of 30 years into a world-renowned

center for forensic sciences.

“Who will replace me, and others like

me?” he asked in his 1994 memoirs, Dead Men Do Tell Tales. “Who

will hire the students I train? I cannot say. The need is there. It cries

out to heaven.”

Today, Maples would be proud of his legacy

to the university. Instead of languishing with his passing, forensic sciences

at UF are flourishing at the William R. Maples Center for Forensic Medicine.

The center integrates the work of the Department

of Anthropology’s C.A. Pound Human Identification Laboratory, which Maples

established, the Department of Pathology, Immunology and Laboratory Medicine’s

Forensic Toxicology Laboratory and numerous other departments to create one

of the country’s most comprehensive forensic medicine programs.

From 1968 until his death from brain cancer

at age 59, Maples participated in more than 1,200 active and historic cases,

including such notables as Czar Nicholas and his family, President Zachary

Taylor, “Elephant Man” Joseph Merrick and Spanish explorer Francisco

Pizarro.

Now, anthropologist Anthony Falsetti and

toxicologist Bruce Goldberger are continuing and expanding on that tradition

as co-directors of the Maples Center.

Viewers of shows like The X-Files or the

popular new drama Crime Scene Investigation may think forensic science and

medicine are only about murder investigations. But, by definition, “forensic”

involves any application of science to law.

At the Maples Center, this definition has

been refined to focus primarily on forensic medicine.

“The Maples Center is unique because

of its emphasis on the field of human medicine. We have the resources at the

university to study and teach forensic medicine,” says Goldberger, citing

the university’s already-strong programs in anthropology, toxicology,

pathology, psychiatry, chemistry, dentistry, nursing and other disciplines.

While Falsetti carries on Maples’ work

with bones at the Pound Laboratory, Goldberger has added his expertise in

soft tissue and fluids at the Forensic Toxicology Laboratory.

“The very theoretical biological issues

that we address also have very practical applications,” says Falsetti.

“And they have to hold up to the most severe type of peer review imaginable

— a court of law.”

Perhaps nowhere on campus do the university’s

missions of teaching, research and service intersect as well as they do at

the Maples Center. Students routinely participate in research that ultimately

results in techniques that aid law enforcement.

Perhaps nowhere on campus do the university’s

missions of teaching, research and service intersect as well as they do at

the Maples Center. Students routinely participate in research that ultimately

results in techniques that aid law enforcement.

Although Maples trained dozens of undergraduate

and graduate students during his years at UF, most of them were anthropology

students. Falsetti and Goldberger are developing a more specialized graduate

program in forensic medicine that could lead to a job in a wide range of fields.

“There is great demand nationally for

broadly trained forensic scientists, teachers, technicians and professionals,”

Falsetti says. “Our goal is to train students in both basic and applied

research to help meet this demand.”

In addition to degree programs, the Maples Center

plans to offer special seminars and continuing education programs for people

already working in the field.

In addition to degree programs, the Maples Center

plans to offer special seminars and continuing education programs for people

already working in the field.

“This service has been repeatedly called

for by Florida’s medical examiners, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement

and various local law enforcement agencies,” Goldberger says, adding

that the Florida Sheriffs Association has endorsed the center’s statewide

mission.

To remain

responsive to its various constituencies, the center has created an advisory

board that includes forensic science experts from many specialties and professions

at the university, in the community and from around the state.

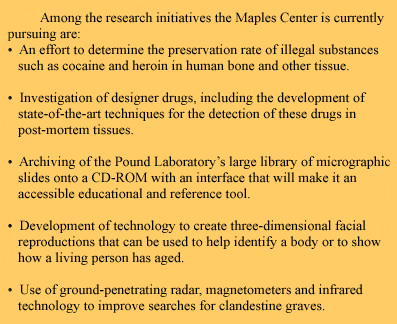

While they are developing the educational

component of the center, Falsetti and Goldberger continue to conduct research

and provide service to law enforcement that have always been central to forensic

sciences at UF.

The Forensic Toxicology Laboratory tests

samples for about a third of the medical examiners in Florida, handling about

2,400 cases a year. And the Pound Laboratory regularly consults with law enforcement

agencies regarding human remains.

Invasion Of The Body Snatchers

Police and forensic anthropologists often

are frustrated by the way Florida’s wildlife eats and scatters human

remains, making it difficult — if not impossible — to determine

whether the person was a victim of an accident or foul play, or even where

the death occurred.

So Falsetti is using the vast Austin Cary

Forest near Gainesville as a natural laboratory and the bodies of pigs as

substitute victims to see how the call of the wild and nature’s forces

can alter the remains of a human being.

“Everybody has different stories about

buzzards and dead bodies, and we have a lot of wildlife in Florida that will

carry off remains,” Falsetti says.

By determining what happens naturally to

a body, Falsetti hopes to be able to tell medical examiners, law enforcement

officers and others when something is not right.

“People do wander away and die naturally,

but if somebody has revisited a scene, it may show that they tried to hide

the body, which addresses the issue of intent,” he says.

Compounding a detective’s problems

caused by wandering critters are the Sunshine State’s muggy climate,

sandy soil and rapidly growing vegetation, adds Mike Warren, an assistant

professor of anthropology working on the project.

“Much depends on the body’s location,

the climate, moisture, rainfall, the population of scavengers and what insects

can be found,” Warren says. “The reason we did the study is we need

to know what happens in Florida.”

One case Falsetti is researching involves

a badly burned body found chained to a tree, surrounded by burned insects.

“Because we know that insects come

to a body after death, there’s something about the time frame, the sequence

of events, that will help law enforcement in terms of charging an individual,”

he says. “Not only did the perpetrator kill the person, but they returned

later to try to alter the scene.”

One of the study’s main findings so

far is that searches for skeletons usually need to be extended over a much

greater area than previously believed.

“This kind of work is important because

we do get a number of calls about informants who say they didn’t do it,

but ‘know’ or ‘heard’ where a body is located,” he

says. “With a little background research, we might be able to help recover

the body.”

Warren is working on another project with

physics Professors Gene Dunnam and Henri Van Rinsvelt that uses a particle

accelerator to verify that ashes returned from a crematory are actually cremated

remains and even to help identify a person based on his or her ashes.

The process is expected to play a role in

resolving an escalating number of disputes nationally over so-called “cremains”

among families or between families and crematories. Such disputes are becoming

increasingly common as more people choose cremation over burial.

Warren and Falsetti sought the physicists’

assistance as part of their work as expert witnesses in a legal battle in

South Florida, where two family members were fighting over the cremated remains

of a loved one. One gave the other an urn, but the recipients suspected its

brownish-white contents were not what they appeared and turned to UF for help.

Traditional cremations leave behind small

bone fragments that forensic workers can readily identify as human bone. But

new technology has resulted in much finer remains with no recognizable bone

or human structure. Because cremation destroys all DNA, forensic scientists

are running out of ways to discriminate between cremated remains and sand.

“The latest cremation technology kind

of put us out of business,” Warren says.

Enter the physicists. Dunnam, Van Rinsvelt

and Ivan Kravchenko, a senior engineering technician, knew particle accelerators

had been used to identify trace elements in geological samples, so they decided

to try using a process known as Particle Induced X-ray Emission analysis,

or PIXE, with the disputed remains.

The physicists’ experiment showed that

the ashes from the South Florida family contained calcium, which would be

consistent with human bone. But it also showed that the ashes did not contain

phosphorus, another common ingredient in bone.

Their conclusion: The urns did not contain

human remains.

“We think it’s a mixture of sandy

soil with a little lime rock,” Dunnam said. “Whoever did this was

not entirely stupid, because lime rock contains calcium, which is also in

bone.”

In certain circumstances, the technique

may open a door for forensic scientists to identify individuals based on their

remains, Falsetti and Warren say. For example, if the deceased had a metal

implant, the particle accelerator also would pick up trace concentrations

of the metal, even if the visible metal lumps were removed following the cremation.

Ecstasy And Agony

While Falsetti’s specialty is anatomical

remains, Goldberger focuses on chemical remains. Lately, much of that research

has been on designer drugs, particularly Ecstasy and some deadly copycats.

Goldberger’s investigation of a string

of drug-related deaths in central Florida last summer has brought him the

kind of media attention Maples used to routinely attract. As director of the

laboratory that identified a deadly new type of drug being sold to unsuspecting

customers as Ecstasy, Goldberger has been featured in newspaper and television

stories nationally.

Until last summer, few people in the Florida

drug scene even recognized the risk of getting impure Ecstasy. Then, in a

two-month period, at least six people died after taking what they thought

was Ecstasy.

“It all started when the Leesburg Medical

Examiner’s Office asked us to help determine what had killed a young

woman in Clermont, Florida,” Goldberger says.

Police thought the woman had overdosed on

Ecstasy, but Goldberger determined that the drug that killed her was para-methoxyamphetamine

(PMA), a drug so new that even Goldberger, who performs more than 2,000 drug

tests a year, had not seen it before.

Goldberger has been leading efforts to educate

users of Ecstasy and other designer drugs to the inherent dangers, but he

says new variations come out as fast as toxicologists can identify them.

Reminiscent of Maples’ work on historically

significant cases, Goldberger also is participating in efforts to determine

whether the man who confessed to being the infamous Boston Strangler actually

committed the crimes.

Goldberger was invited to be part of a team

examining the remains of 19-year-old Mary Sullivan, who was found strangled

in her apartment in January 1964. New evidence suggests that Albert DeSalvo,

the man who confessed to being the Boston Strangler and killing Sullivan and

a dozen other women, was lying.

Goldberger’s role is to determine if

there were any drugs or alcohol present in Sullivan’s system when she

died. Although no one believes Sullivan used drugs or alcohol, one theory

is that the killer drugged her.

“The person who killed her may have

been with her for some time,” Goldberger says. “It is possible there

may have been something put in her drink. Those are the kinds of facts we

are attempting to clarify.”

Aaron Hoover contributed to this article.

Anthony B. Falsetti

Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology

(352) 392-6772

falsetti@ufl.edu

Bruce A. Goldberger

Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, “Immunology and

Laboratory Medicine

(352) 846-1579

bruce-goldberger@ufl.edu

Related web site:

http://maples-center.ufl.edu