|

32 Faculty

Named UF Research Foundation Professors

click here to see

professor list

The University of Florida Research Foundation (UFRF) has named 32 faculty

members who have a distinguished current record of research and a strong

research agenda that is likely to lead to continuing distinction in their

fields as UFRF Professors for 2001-2004.

The UFRF professors were recommended by their college deans based on nominations

from their department chairs, a personal statement and an evaluation of

their recent research accomplishments as evidenced by publications in

scholarly journals, external funding, honors and awards, development of

intellectual property and other measures appropriate to their field of

expertise. The three-year award carries with it a $5,000 annual salary

supplement and a $3,000 grant.

“Much of the information in the nomination packets comes from department

chairs and colleagues who know better than anyone the status these researchers

have achieved in their respective fields,” said Win Phillips, vice

president for research. “Words like ‘cutting edge,’ ‘innovative,’

‘most productive’ and ‘revolutionary’ are testament

to the respect these peers have for their colleagues.

“Another constant among UFRF Professors is the importance they place

on teaching,” Phillips added. “Despite often extensive research

activities, these faculty are often also the recipients of outstanding

teaching awards.”

The professorships are funded from the university’s share of royalty

and licensing income on UF-generated products.

$3.9

Million Grant To Fund New Agroforestry Center

by Tom Nordlie

To promote environmentally friendly farming practices in the Southeast,

the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences

is establishing a new Center for Subtropical Agroforestry with the aid

of a $3.9 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

P.K. Nair, distinguished professor in the School of Forest Resources and

Conservation, said the center will provide teaching, research and extension

in agroforestry, a new farming practice that grows crops and animals alongside

of trees or shrubs.

“We’ve waited years for this,” said Nair, who will serve

as the center’s director. “It’s the first time a government

agency has provided substantial funding for agroforestry in the southeastern

U.S.”

He said scientific agroforestry practices are relatively unknown to industrialized

nations but are common in tropical regions, where limited-resource farmers

grow trees in crop fields to produce firewood and other products.

“In the United States, agroforestry could bridge the gap between

commercial agriculture and traditional farming,” Nair said. “It

could help smaller farms diversify, enhance revenues and become more sustainable.

It also promotes conservation of land and wildlife habitat.”

To give the center a regional perspective, UF experts will collaborate

with representatives of Florida A & M University, Auburn University,

the University of Georgia and the University of the Virgin Islands.

The center will pursue eight research projects and four extension projects.

One research project involves farming pine trees on cattle pastureland.

Another will focus on interaction between trees and crops, which often

compete for resources.

Before the public supports agroforestry, it must become aware of it, said

Alan Long, UF associate professor of forest operations. Long and UF natural

resources assistant Professor Martha Monroe are coordinating the center’s

four extension projects with the help of Sarah Workman, a newly recruited

research assistant professor with the agroforestry center.

One extension project will establish demonstration areas on farms where

landowners can view agroforestry cultivation, Workman said.

P.K. Nair, pknair@ufl.edu

Genetically

Modified Earth Plants Will Glow From Mars

by Paul Kimpel

In what reads like a story from a 1950s science fiction magazine, a team

of University of Florida scientists has genetically modified a tiny plant

to send reports back from Mars in a most unworldly way: by emitting an

eerie, fluorescent glow.

If all goes as planned, 10 varieties of the plant could be on their way

to the red planetas part of a $300 million mission scheduled for 2007.

The plant experiment, funded by $290,000 from NASA's Human Exploration

and Development in Space program, may be a first step toward making Mars

habitable for humans, said Rob Ferl, assistant director of the Biotechnology

Program at UF.

Ferl and a team of molecular biologists chose as their subject the Arabidopsis

mustard plant. They picked it, Ferl said, because of three attributes

that make it ideally suited for the Mars mission: its maximum height is

8 inches, its life cycle is only one month and its entire genome has been

mapped. Moreover, in December 2000 it became the first plant to have its

genetic sequence completed.

To create the glow, the team will insert "reporter genes" into

varieties of the plant that will express themselves by emitting a colored

glow under adverse conditions on Mars. Each reporter gene will react to

an environmental stressor such as drought, disease or temperature. For

example, one version will glow an incandescent green if it detects an

excess of heavy metals in the Martian soil; another will turn blue in

the presence of peroxides.

Ferl's team, in collaboration with Andrew Schuerger, a manager of Mars

projects at the Kennedy Space Center-based Dynamac Corp., is competing

with other biologists to receive the NASA contract for the Mars trip.

.

The 2 1/2-year Mars mission — nine months traveling 286 million miles

each way and one year stationed on the planet - would work like this:

The seeds of the plant would make the trip aboard a spacecraft similar

to NASA's Mars Odyssey, which was launched April 7. Upon arrival, the

landing vehicle's robot would scoop up a portion of Martian soil, and

the scientists would analyze it using the robot and a specialized camera.

After modifying the soil with fertilizers, buffers and nutrients, the

scientists will germinate the seeds and grow the plants in a miniature

greenhouse on the landing vehicle.

Rob Ferl, robferl@ufl.edu

Andrew Schuerger, chueac@kscems.ksc.nasa.gov

UF Seeks

To Preserve Historic Cuban Archive

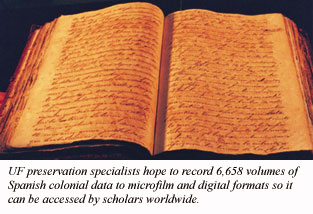

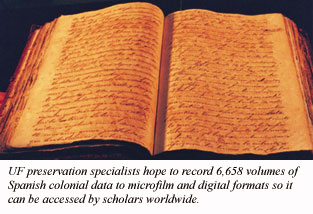

The

University of Florida is launching an effort to preserve and make accessible

a veritable gold mine of rare historic documents in Cuba's National Archives

that chronicle three centuries of Spain's colonization of the New World. The

University of Florida is launching an effort to preserve and make accessible

a veritable gold mine of rare historic documents in Cuba's National Archives

that chronicle three centuries of Spain's colonization of the New World.

Known as the Notary Protocols, these archival holdings in Havana are bound

in 6,658 tomes, each containing an estimated 1,300 handwritten pages (the

equivalent of about 40,000 volumes in a modern library). They track the

comings and goings of many ships that sailed and nearly every person who

traveled between Spain and the New World from the 16th through 19th centuries,

said John Ingram, director of library collections at UF's George A. Smathers

Libraries.

"We are embarking on a unique opportunity that will benefit present

and future generations of scholars, students and the interested public,"

Ingram said.

The preservation effort will bring both microfilm and digital technology

to bear on the archives' deteriorated papers. When funding is secured,

specialists will travel to Havana and begin a 12- to 18-month pilot program

for the lengthy and painstaking process of transferring the entire collection

to microfilm and digital formats. Afterward, a guide to the materials

will be posted on the Internet, and users will be able to obtain copies

of individual documents on compact disc.

The project is the result of an agreement signed in March by UF and the

Cuban National Archives. Ingram said the documents are especially relevant

to Florida, where notary archives for the First Spanish Period (1565-1764)

were lost during the U.S. invasion of Florida in 1812. The Notary Protocols

will likely contain information on the outfitting of early expeditions

to Florida and underscore the great dependence that Florida had on Cuba

in almost all aspects of Spanish colonial life.

For more than 300 years, notaries in Havana recorded detailed information,

dutifully registering travelers' wills, legal documents and the cargos

they might be carrying. The result, Ingram said, is a priceless archive

of materials that many specialists regard as the single most important

source of information on the New World's colonial history. Regarded as

uniquely valuable to this history for more than 100 years, yet rarely

consulted because of their location and a general lack of resources to

expose their value to scholars, the thousands of tomes will be a genuine

treasure for research.

The cost of the project will be paid for with money raised from foundations

and private donations, Ingram said. No federal or state tax dollars will

be used. With the completion of a successful pilot program, and to make

the larger effort possible, the UF library seeks to team up with U.S.

and Spanish libraries and institutions in enlisting funding support for

the entire project.

"I am convinced that the Protocolos Notariales in Cuba's archives

will assume their rightful place of global importance for New World history

and culture," Ingram said. "For my colleagues in Latin American

studies, these records will truly open a window in time."

John Ingram, jeingr@mail.uflib.ufl.edu

Peppers

Rely On "Zing" To Spread Seeds

by Aaron Hoover

It adds the fire to chili and the hot to salsa, but what does the zing

do for the pepper?

As it turns out, quite a lot. Working with the ancestor of most varieties

of chili pepper plants, a University of Florida researcher has shown that

the plant relies on its spiciness to ensure the very survival of its species.

In

an article in the journal Nature in July, Josh Tewksbury, a UF postdoctoral

researcher in zoology, and co-author Gary Nabhan, an ethnobotanist at

Northern Arizona University, conclude that mammals, sensitive to the chemical

that makes peppers taste hot, avoid the Capsicum annuum pepper. Birds,

however, are unaffected by the chemical, known as capsaicin, and they

happily eat the peppers. This is essential for the plant, since birds

release the seeds in their droppings ready to germinate - whereas if mammals

ate the seeds, they would crunch them up or render them infertile, the

researchers report. In

an article in the journal Nature in July, Josh Tewksbury, a UF postdoctoral

researcher in zoology, and co-author Gary Nabhan, an ethnobotanist at

Northern Arizona University, conclude that mammals, sensitive to the chemical

that makes peppers taste hot, avoid the Capsicum annuum pepper. Birds,

however, are unaffected by the chemical, known as capsaicin, and they

happily eat the peppers. This is essential for the plant, since birds

release the seeds in their droppings ready to germinate - whereas if mammals

ate the seeds, they would crunch them up or render them infertile, the

researchers report.

"The upshot is that it's very beneficial for the pepper to have mammals

avoid its fruit and have birds attracted to them," Tewksbury said.

Plants that produce apparently poisonous or undesirable fruits - the edible

reproductive body of a seed plant - have long puzzled biologists. Evolutionary

theory says the main reason that plants create fruits is to encourage

animals to eat them, so that the animals will disperse the plant's seeds.

Why, biologists wonder, would plants go to the trouble of making a fruit,

only to use chemicals to deter an animal and potential seed distributor?

Evolutionary biologist Dan Janson proposed in the late 1960s that plants

may use chemicals to deter some animals without deterring others, thus

selecting only preferred seed distributors. Known as "directed deterrence,"

this theory received very little attention and was never observed in nature,

and it gathered dust in scholarly journals until Tewksbury and Nabhan

decided to see if it might hold true in chili peppers.

The researchers did their investigation in a field in southern Arizona

about 35 miles south of Tucson, using the Chiltepine chili pepper, Capsicum

annuum. The plant is the progenitor of virtually all peppers native to

North America, including jalapeno, poblano and bell peppers.

Using video cameras trained on the plants, they discovered that birds

- in particular, a species known as the curve-billed thrasher - were the

only animals eating the small, red peppers. Meanwhile, pack rats and cactus

mice, the dominant fruit- or seed-eating mammals in the area, avoided

the peppers entirely.

That was fine as far as it went, but Tewksbury and Nabhan needed to prove

that the rats and mice were avoiding the capsaicin chemical in the peppers.

To do so, they found a pepper similar in size, shape and nutritional content

to Capsicum annum. But because of a genetic quirk, the pepper,

a variety of Capsicum chacoense, completely lacks capsaicin.

The researchers fed this "spiceless" pepper to packrats, mice

and birds in labs. All gobbled it up. When the researchers swapped the

hot pepper with the spiceless pepper, the birds continued to eat the pepper,

but the rodents refused to even nibble it.

Analyzing the droppings and feces of the birds and rodents, the researchers

discovered that the birds passed the seeds whole and capable of germinating.

The rodents, however, chewed up most of the seeds, and any that remained

were too damaged to germinate.

To cap it off, Tewksbury and Nabhan discovered that the curve-billed thrashers

tended to spend a lot of time on a variety of fruiting shrubs, frequently

releasing their droppings there. The peppers, they discovered, grew much

better in the shade of the shrubs than the hostile open desert, which

comprises the majority of habitat. The chilies also have two additional

advantages: Birds are more likely to eat the pepper from chili bushes

growing near the shrubs, further dispersing the seed, and an insect that

kills the seeds and fruit of the pepper was much less common in the shade

of the shrubs.

So not only are the birds distributing undamaged pepper seeds, they are

doing so in just the places the resulting plants are most likely to thrive,

Tewksbury said.

"From the pepper's perspective, it's very beneficial to get pooped

out as a seed underneath a shrub, particularly a shrub that has fleshy

fruits itself, and that's just where the thrashers deposit the seed,"

he said.

Josh Tewksbury, jtewksbury@zoo.ufl.edu

Mysterious

Brown Dwarfs Are Likely "Failed Stars"

by Aaron Hoover

An

international research team led by University of Florida astronomers announced

in June that it had found dusty disks surrounding numerous faint objects

believed to be "brown dwarfs" in the Orion Nebula. An

international research team led by University of Florida astronomers announced

in June that it had found dusty disks surrounding numerous faint objects

believed to be "brown dwarfs" in the Orion Nebula.

Brown dwarfs, first observed about a decade ago, are mysterious gaseous

structures that do not shine from sustained nuclear fusion as stars do.

The findings of the new study suggest brown dwarfs may be more similar

to "failed stars" rather than to "super planets,"

forming from collapsing clouds of interstellar gas.

That means brown dwarfs, like stars, could have planets rotating around

them - although, without a proper sun, the planets likely wouldn't provide

an environment conducive to life, said Elizabeth Lada, a UF associate

professor of astronomy.

"It is entirely possible that our galaxy contains numerous planetary

systems that orbit these cold, dark, failed stars," Lada said. "But

even if brown dwarfs do have planetary systems, their planets would not

have a stable climate and thus would be inhospitable to life as we know

it."

The team, which announced its findings at the American Astronomical Society

meeting in Pasadena, Calif., based its conclusions on observations of

likely brown dwarfs in the so-called Trapezium cluster, a group of extremely

young stars within the Orion Nebula. Located about 1,200 light years from

Earth, the cluster and nebula appear to the untrained eye as a single

central star in the sword of the hunter in the constellation Orion. The

cluster is a kind of stellar nursery, with most of its stars aged less

than 1 million years old, in contrast to our middle-aged sun, which is

4 billion years old.

Stars are thought to form when gravity causes a rotating cloud of gas

to contract. Before the actual star is formed, the gas collapses into

a rotating disk. Most young stars observed to date have been accompanied

by such disks. Using a state-of-the-art, near-infrared camera on a European

Southern Observatory telescope in the Chilean Andes, the researchers found

disks surrounding both young stars and suspected brown dwarfs in the Trapezium

cluster. Moreover, the percentage of stars with disks matched the percentage

of brown dwarfs with disks.

That suggests brown dwarfs and stars share a common origin - one different

from planets, which form within disks surrounding stars but do not have

disks of their own. The observation is important because the small size

of brown dwarfs - they are less than 7 percent of the size of our sun

- had led some astronomers to speculate they were related more closely

to planets than stars.

The team also achieved another milestone. In analyzing the observations,

the astronomers identified at least 80 likely brown dwarfs, roughly doubling

the number of the structures identified so far. The brown dwarfs in the

Trapezium cluster constitute the largest "population" of brown

dwarfs ever observed, researchers said.

"Even at their brightest, most brown dwarfs are still 100 or more

times fainter than our sun, explaining why astronomers find such objects

so difficult to detect," said August Muench, a UF doctoral student

in astronomy and the project's lead investigator.

Elizabeth Lada, lada@astro.ufl.edu

Coastal

Ecosystems Collapse Tied To Past Overfishing

by Aaron Hoover

Dying

coral reefs, dwindling shellfish populations, shrinking seagrass beds

and other collapses of the world's coastal ecosystems are often blamed

on pollution or global warming. Dying

coral reefs, dwindling shellfish populations, shrinking seagrass beds

and other collapses of the world's coastal ecosystems are often blamed

on pollution or global warming.

But in a paper that appeared in the journal Science in July, 16

scientists and academicians from around the world argue that these trends

were set into motion by a much older human transgression: overfishing.

Beginning long before Columbus and accelerating rapidly in colonial and

modern times, people have radically overfished marine mammals, large fishes

and shellfish, according to the paper, whose co-authors include Karen

Bjorndal, a zoology professor and director of the Archie Carr Center for

Sea Turtle Research at the University of Florida.

The reduction of these animals to a fraction of their historical abundance

has caused ecological damage that remained hidden until recent decades,

when other circumstances triggered its full effects, the scientists say.

"What we're finding is a number of the crises that our marine ecosystems

are facing today can be traced back thousands of years in some cases,

and hundreds of years in others, to when human beings first began affecting

these ecosystems," Bjorndal says.

The paper discusses coastal ecosystems around the globe, hopscotching

from the Chesapeake Bay to the Caribbean to Australia's coastal waters.

It steps outside the bounds of pure ecological science, drawing on a broad

array of scientific literature, historical accounts and archaeological

evidence of aboriginal fishing practices.

The authors tie several recent downturns in the world's coastal ecosystems

to past overfishing. Examples include declining underwater kelp forests,

declining shellfish beds and shrinking seagrass beds.

Bjorndal's research ties overfishing of green sea turtles to the decline

of turtlegrass in Florida Bay and in the Caribbean. The turtles, which

eat only plants, prevent the turtlegrass from growing too long. In their

absence, the longer grass shades the bottom, slows the current and decomposes

on the sea bottom. This process both increases nutrients and encourages

turtlegrass diseases.

"One of our best estimates is that green sea turtle populations today

are 5 to 10 percent of what they were when Columbus arrived," Bjorndal

says. "The functional loss of this species has had a huge effect."

Despite evidence of massive declines in many populations, the authors

say most of the overfished species still survive in sufficient numbers

to permit restoration.

"If we want to restore these ecosystems, we have to understand how

they function, and just looking back a couple of decades isn't going to

tell us," Bjorndal says.

Karen Bjorndal, kab@monarch.zoo.ufl.edu

|

University

of Florida engineering researchers have developed an inexpensive system

to count red-light runners at intersections, a step that comes as advocates

of red-light camera ticketing systems pursue laws making them legal in

Florida.

University

of Florida engineering researchers have developed an inexpensive system

to count red-light runners at intersections, a step that comes as advocates

of red-light camera ticketing systems pursue laws making them legal in

Florida.

The

solution to one of man’s most vexing environmental problems may lie

in one of nature’s most remarkable plants.

The

solution to one of man’s most vexing environmental problems may lie

in one of nature’s most remarkable plants.

The

University of Florida is launching an effort to preserve and make accessible

a veritable gold mine of rare historic documents in Cuba's National Archives

that chronicle three centuries of Spain's colonization of the New World.

The

University of Florida is launching an effort to preserve and make accessible

a veritable gold mine of rare historic documents in Cuba's National Archives

that chronicle three centuries of Spain's colonization of the New World. In

an article in the journal Nature in July, Josh Tewksbury, a UF postdoctoral

researcher in zoology, and co-author Gary Nabhan, an ethnobotanist at

Northern Arizona University, conclude that mammals, sensitive to the chemical

that makes peppers taste hot, avoid the Capsicum annuum pepper. Birds,

however, are unaffected by the chemical, known as capsaicin, and they

happily eat the peppers. This is essential for the plant, since birds

release the seeds in their droppings ready to germinate - whereas if mammals

ate the seeds, they would crunch them up or render them infertile, the

researchers report.

In

an article in the journal Nature in July, Josh Tewksbury, a UF postdoctoral

researcher in zoology, and co-author Gary Nabhan, an ethnobotanist at

Northern Arizona University, conclude that mammals, sensitive to the chemical

that makes peppers taste hot, avoid the Capsicum annuum pepper. Birds,

however, are unaffected by the chemical, known as capsaicin, and they

happily eat the peppers. This is essential for the plant, since birds

release the seeds in their droppings ready to germinate - whereas if mammals

ate the seeds, they would crunch them up or render them infertile, the

researchers report. An

international research team led by University of Florida astronomers announced

in June that it had found dusty disks surrounding numerous faint objects

believed to be "brown dwarfs" in the Orion Nebula.

An

international research team led by University of Florida astronomers announced

in June that it had found dusty disks surrounding numerous faint objects

believed to be "brown dwarfs" in the Orion Nebula. Dying

coral reefs, dwindling shellfish populations, shrinking seagrass beds

and other collapses of the world's coastal ecosystems are often blamed

on pollution or global warming.

Dying

coral reefs, dwindling shellfish populations, shrinking seagrass beds

and other collapses of the world's coastal ecosystems are often blamed

on pollution or global warming.