Conversations

With Hiram: Reflections Of An Artist

Conversations

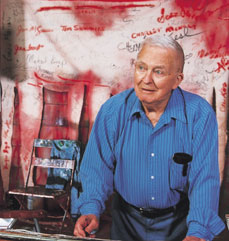

With Hiram: Reflections Of An ArtistProfessor Emeritus Of Art Hiram Willliams Looks Back On Half A Century Of "Suggestive Painting"

by Margaret Ross Tolbert

|

|

Conversations

With Hiram: Reflections Of An Artist

Conversations

With Hiram: Reflections Of An Artist

Professor

Emeritus Of Art Hiram Willliams Looks Back On Half A Century Of "Suggestive

Painting"

by

Margaret Ross Tolbert

Hiram

Williams’ studio

is small and windowless, illuminated by a skylight and some jerry-rigged

overhead lights, a paint-spattered chair and a drawing board dominating.

Paintings that went on to hang in places like The Museum of Modern Art

and the Guggenheim first hung here on a battered piece of green plywood.

But limited space and simplicity of means are no obstacle to Williams’

creativity. Thousands of drawings and paintings have emerged from this

one-room crucible for his searing, distinctive imagery.

A few tubes of oil paint, charcoal, graphite, brushes in a soup of mineral

spirits and turpentine. That’s all it takes for Hiram Williams to

turn an idea into a painting.

“I use oil, graphite and collage now and then,” Williams says.

“Marks and shapes are functional and do things visually: They create

tension, they hold positions, they suggest directions, they do all of

these besides illustrating descriptive or abstract appearance.”

As

students years ago, each weekly visit to Williams’ studio exposed

us to a new volley of tough and daring imagery, and left many of us convinced

that nothing in life had as much potential for expression as a painting

the way Hiram Williams did it.

As

students years ago, each weekly visit to Williams’ studio exposed

us to a new volley of tough and daring imagery, and left many of us convinced

that nothing in life had as much potential for expression as a painting

the way Hiram Williams did it.

Process painting, where the artist discovers the true subject of a painting

through the act of painting it, usually results in paintings of insistent

and unrelenting abstraction. But Williams uses process painting to capture

a world of totally unexpected subjects: portraits of students, bananas,

rocks, mountainsides, bouquets, meat tables, and his trademark images

of the human figure, in which he inveighs against the political climate

and man’s inhumanity to man.

During filming recently of a documentary to accompany Art/Life: The

Painting of Hiram Williams, a new retrospective on his work at UF’s

Harn Museum of Art from August 26 to October 28, Williams discussed at

length his philosophies of art. Although some have changed significantly

over the years, many of his tenets remain the same: A painting, he says,

is nothing but pigment on a surface. The artist has to acknowledge that

“picture plane” as he creates the illusion of pictorial depth.

It is the dichotomy between these two, illusion and flatness, that makes

a painting a special entity.

A painting is finished, Williams taught us, when it has formal unity,

the forms working together like a well-oiled machine. Every form in the

painting had to be integral to the piece. Its loss would, like pulling

a can out of a pyramid in a grocery store display, collapse the visual

structure of the entire painting. During every class, Williams would articulate

his philosophies about painting, leaving them to fester in his students’

minds, emerging in their own work weeks or months later.

ART/LIFE

Williams’ enormous and sustained creativity is no accident.

“I

never had artist’s block,” he says. “In order to have art

pursue you, you’ve gotta pursue art. Give up tennis, give up yachting,

give up vacations, and just work.”

“I

never had artist’s block,” he says. “In order to have art

pursue you, you’ve gotta pursue art. Give up tennis, give up yachting,

give up vacations, and just work.”

Williams maintains that any subject has potential as a metaphor, to become

a painted form that is charged with meaning, that can wring a variety

of emotions from the viewer.

“I am very dependent on the viewer’s reaction,” Williams

says. “The form causes emotional meaning. We look at things and we

react. I give them enough so they can create a gestalt and I want that

gestalt to move them emotionally.”

Williams relentlessly scours all his experiences for new forms of expression.

The simplest of forms can lead to a series, even the head he sees in the

mirror.

“The head, the outline of the head, is my head. I look into the mirror

and shave every day almost and there it is ... that doggone head,”

he says in describing the inspiration for his landmark series of self-portraits.

“I’ve gotten so I could do it with my eyes closed, I think.”

It can be a stump seen in a vacant lot on a daily walk, as in the Orton’s

Stump series. Or the snakes on Paynes Prairie near Gainesville.

“I read somewhere in a scientific journal like National Geographic

that snakes had temperaments much as you and I do as human beings,”

he says. “They were more human than we were, in some ways, and with

that in mind I thought what I’d do was show the snakes in Paynes

Prairie. I used to imagine walking among the snakes and how that would

be.”

Williams explores these ideas initially with small sketches in his journal,

ART/LIFE, of which there are now more than 250. He does some studies

and collages of the subject, some bigger drawings and finally some paintings.

Art

At An Early Age

Hiram Williams was born in Indiana but spent much of his childhood in

Pennsylvania, where he discovered his love of art at an early age.

Drafted in 1941, he married Avonell Baumunk during basic training, then

went off to fight in Europe.

After graduating with a degree in painting from Penn State in 1951, Williams

taught at the University of Southern California and the University of

Texas while Avonell worked and raised their two children, Curtis and Kim.

During

the Texas years, a faculty research grant freed him to concentrate his

phenomenal energy on mammoth canvases of the human figure. These 28 canvases,

completed in just four months, were painted with the brio and vigor of

the abstract expressionists.

During

the Texas years, a faculty research grant freed him to concentrate his

phenomenal energy on mammoth canvases of the human figure. These 28 canvases,

completed in just four months, were painted with the brio and vigor of

the abstract expressionists.

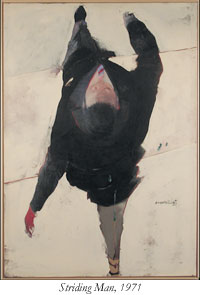

“I painted in the living room,” he recalls, “and Avonell

worked and looked after the kids.” This creative effort paid off

with his breakthrough idea for the OverHead Man series.

“I was trying to show the sides, various views of the figure all

in one in the image without any fractures in it like the cubists did,”

he says.

He used a distorted and distended contour to simultaneously depict all

sides of a “total figure” moving through space. Unlike the cubists,

he kept an unbroken image to suggest the passage of time.

“Picasso would have shown part of the figure and then another part

of the figure, but I show it without any fracturing,” he says.

His work began to attract national attention, and he was accepted in large

exhibitions such as the Carnegie International. Prominent institutions

including the Whitney Museum of American Art and The Museum of Modern

Art in New York acquired his paintings.

Williams came to the University of Florida to teach in 1960, starting

on the same day as renowned photographer Jerry Uelsmann, who eventually

contributed to Williams’ Gazer and Self-Portrait series.

“Jerry Uelsmann made me about a hundred eyes and I cut them out and

I used these eyes to depict my gazers and so forth,” Williams says.

“It’s amazing what one element of the human being can bring

on imaginatively. One eye can get pretty doggone exciting.”

His imagery continued to develop: “I soon discovered that Overhead

Man led to Stroboscopic figures. One man repeated, but not fractured

as in Duchamp’s Nude Descending the Staircase, had all sorts

of possibilities for scale and space. I was led to Running Men and Stretched

Men. I began to realize that I was busy illustrating existential people,

much in keeping with my view of humanity’s plight in the real world.

To my mind, it depicts the tension that we all experience as we live in

modern times.”

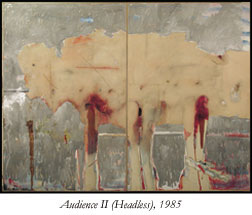

Williams’ imagery now included crowds, initiating the Chorus Line

and Audience series, which he describes as “an effort to look at

my fellow man as a viewer of his own destiny ... in an uncaring world.”

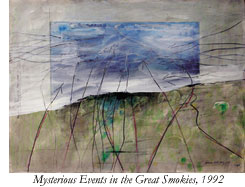

Despite this outlook, Williams’ work is marked increasingly by exuberant

energy. Since retirement in 1982 his repertoire has exploded to include

many new subjects. Not only does he continue his depiction of the human

figure and objects that can be seen as extensions of the figure, such

as the bloody meat table series, he now mines personal experiences in

Florida to image humanity in a subtler and deeper way. Much of this newer

lexicon — bananas, alligators, snakes, crows, shorebirds, beaches,

punchbowls, stumps and palms — is an outgrowth of his encounters

with the North Florida landscape.

“I

identify creatures in Florida with the humanity in Florida,” he says.

“There are a lot of alligators around here and a few snakes, too.

On the whole the snakes are benign and you can run away from the alligators

if you have any sense, and I have run away from alligators snapping at

my feet, you know.”

“I

identify creatures in Florida with the humanity in Florida,” he says.

“There are a lot of alligators around here and a few snakes, too.

On the whole the snakes are benign and you can run away from the alligators

if you have any sense, and I have run away from alligators snapping at

my feet, you know.”

A self-titled “suggestivist,” Williams furnishes minimal cues

about his subjects that reflect their essence, inviting the viewer to

fill in the details.

“I like the idea of the viewer completing the painting visually,”

he says. “For example, there’s an alligator, which I reduced

to just the head and a vague sense of the body in the water as he moves,

and it bears quite a strong resemblance to the real thing.”

Humanity is ever the focus, and in some of his most poignant pieces, such

as Audience Destroying Its Environment, Williams shows us what the audience

does to its world.

“A good piece of art should tell you what it is doing, but a lot

of this is subliminal. You are suddenly aware that you have this new information,

but you have no idea how you got it. Artists could be likened to a man

in a foggy hallway groping about to find a door at the other end.”

Age and a series of ailments have slowed Williams, but he still tries

to paint every day.

Heading to his studio he says “I think I’ll do some landscapes.”

Art/Life:

The Painting of Hiram Williams

August 26 - October 28, 2001

This exhibition pays tribute to Hiram Williams, a master American artist and influential teacher whose works hold a significant place in the Harn Museum of Art collections. The exhibition will draw on the more than 450 paintings, drawings and sketches in the museum's collections and on major new works from the artist's studio. With a special thematic focus on the mentor-student relationship, Margaret Tolbert, an accomplished artist and former student of Williams at the University of Florida, is curator for the exhibition.