Explore Magazine

Volume 6 Issue 2

Mayan

Meltdown

Mayan

Meltdown

UF Geologists' Analysis Of

Ancient Lakebeds Leads To A Theory About The Decline Of Mayan Civilization

by Joseph Kays

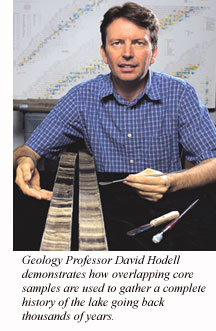

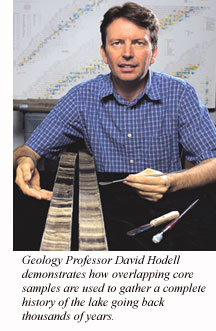

David Hodell, Mark

Brenner and Jason Curtis watched intently as the 1.9-meter-long, clear

plastic tubes of sediment they had worked so hard to extract from

the bed of Mexico's Lake Chichancanab made their way through the GEOTEK

MultiSensor Core Logger.

Every half

centimeter, the state-of-the-art device fired a beam of gamma ray

radiation through the 2-inch-diameter cores, recording 2,600 years

of the lake's history to a computer.

Located in the heart of the Yucatan peninsula near the seat of power

for the northern half of the Mayan civilization that once dominated

Mexico and Central America, Lake Chichancanab's history should mirror

the environment in which the Mayan people of the region lived, the

researchers say.

And the data coming out of the core samples indicated significant

meteorological changes were occurring just as the Maya's life took

a dramatic turn for the worse.

The water in Lake Chichancanab, which means "little sea"

because of it saltiness, is nearly saturated with calcium sulfate,

or gypsum, so when lake water evaporates during dry periods, the gypsum

settles to the lake bottom, forever memorializing that drought in

the sediments.

The

team, part of UF's new Land Use and Environmental Change Institute,

could easily see the strata of white gypsum segmenting the core like

icing between layers in a chocolate cake, but only the sensitivity

of the core logger could map those layers with the precision the three

University of Florida geologists needed to resolve their questions

about climate conditions around Lake Chichancanab during the last

three millennia.

The

team, part of UF's new Land Use and Environmental Change Institute,

could easily see the strata of white gypsum segmenting the core like

icing between layers in a chocolate cake, but only the sensitivity

of the core logger could map those layers with the precision the three

University of Florida geologists needed to resolve their questions

about climate conditions around Lake Chichancanab during the last

three millennia.

The May 2000 expedition to Chichancanab was the second the team made

to the region. Core samples collected during a 1993 expedition revealed

that the period between 800 and 1000 A.D. was the driest in 7,000

years in the region, leading them to publish a paper in the journal

Nature that suggested drought conditions contributed to the decline

of the Maya civilization.

But

although the scientists were able to identify dry periods from the

1993 samples, the cores and the technology to study them lacked detail.

But

although the scientists were able to identify dry periods from the

1993 samples, the cores and the technology to study them lacked detail.

"From

our earlier research, we knew there was a drought, but we had no clues

as to its cause," says Hodell.

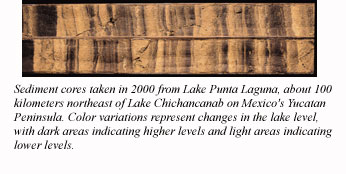

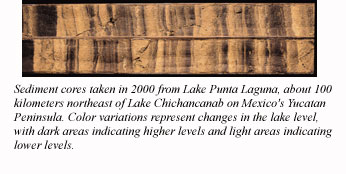

So, with

funding from the National Science Foundation Paleoclimate Program, they

returned to Lake Chichancanab and Punta Laguna in 2000 to get more samples.

These Chichancanab samples yielded considerably more seeds and other

organic matter that could be dated using radiocarbon techniques. The

new dates and improved technology - like the MultiSensor Core Logger

purchased with a $170,000 grant from the UF Opportunity Fund - allowed

them to develop a more detailed and accurately timed chronology of the

droughts.

"With

these new cores and the high-resolution density records we generated,

we were able to detect cycles in the record," Hodell says.

"With

these new cores and the high-resolution density records we generated,

we were able to detect cycles in the record," Hodell says.

The dominant

cycle they found, of recurring droughts on the peninsula every 208 years,

"caught our attention," Hodell says, "because it is close

to a 206-year cycle that is thought to be due to variations in solar

intensity."

Burned

By The Sun God?

For 600 years, the Maya represented the height of pre-Columbian culture

in present-day Central America. During this "Classic Period,"

the Maya achieved great advances in science, architecture and social

organization. They mapped the heavens and developed extremely accurate

calendars; built elaborate temples, palaces and observatories; and established

complex societies.

Then, between 750 and 900 A.D., the Mayan civilization all but disappeared.

Construction of ceremonial buildings stopped and hieroglyphic writings

ceased.

Anthropologists, archaeologists and historians have debated the decline

of the Maya for a century, focusing primarily on social upheaval as

the root cause. Only recently have physical scientists like the UF researchers

entered the fray.

Archaeologists know the Maya were capable of precisely measuring the

movements of the sun, moon and planets, but Hodell said he is unaware

of any evidence the Maya knew about the bicentennial cycle that ultimately

may have played a role in their downfall.

"It's

ironic that a culture so obsessed with keeping track of celestial movements

may have met its demise because of a solar cycle," he says.

Hodell is the first to admit that he and his colleagues "aren't

really the experts on the human side. We provide a climate context for

the archaeologists. It's up to them to determine whether it has any

bearing on the civilization. Our data present a challenge to archaeologists

to look for evidence of human response to drought.

"The collapse of any civilization is a complex issue, and it would

be an oversimplification to attribute it to any single cause,"

says Hodell, "but we believe drought could be a root cause that

tipped the balance.

"Rapid growth of the Maya population during the Classic Period

may have strained the carrying capacity of the land, then the drought

comes and it triggers a cascade of events - decreasing agricultural

yields, malnutrition, increased competition for resources and warfare,

and general social upheaval," he continues.

The researchers say response to their theory has been mixed, particularly

among social scientists.

"Some people liked the premise," Hodell says, "while

others thought we were heretics."

"We didn't really change anyone's mind," Brenner adds. "People

who were inclined to focus on social phenomena stuck to their guns.

But it is difficult to deny the role of environment. It seems obvious

that culture is intimately connected to the environment."

Earth is currently in the middle of the 206-year solar cycle, Hodell

says, adding that even a severe drought today isn't likely to have the

same impact on a culture as in ancient times.

Brenner noted North Korea currently is suffering an extreme drought,

but the country has the benefit of international aid.

"Nobody stepped in to help the Maya out," he said, "and

as conditions worsened, it probably created a lot of stress among various

Maya cities competing for resources."

The research team is already analyzing core samples gathered from other

parts of Central America to confirm the existence of the 208-year drought

cycle. They hope this data can be used by climatologists and atmospheric

physicists to determine why a small increase in solar output had such

a large impact on the Central American climate.

Aaron

Hoover contributed to this article.

David

Hodell

Professor, Department of Geology

(352) 392-6137

dhodell@geology.ufl.edu

Mark

Brenner

Assistant Professor, Department of Geology

(352) 392-2231

brenner@ufl.edu

Maya

Perspective

Maya

Perspective

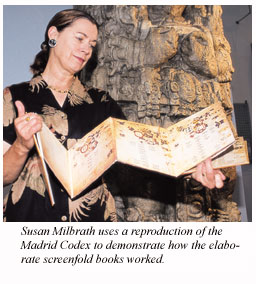

By Susan Milbrath

My geologist husband,

Mark Brenner, and his colleagues, David Hodell and Jason Curtis, have

used geologic samples and astronomical cycles to develop a theory about

the role a drought caused by increased solar activity played in the

collapse of the Mayan civilization.

My work also involves the study of astronomy, but I take the perspective

of the Maya. Studying their art, calendar and folklore has helped me

reconstruct important elements of Maya astronomy. The discovery of the

"solar forcing" cycle now leads me to pose two anthropological

questions.

Did the Classic Maya record the dramatic changes in the weather seen

in the geological record?

The answer is both yes and no. What the Maya weren't writing about alludes

to changes in their culture more than what they were writing about.

For example, the Maya abruptly stopped erecting monuments with written

inscriptions in the ninth century, indicating some sort of cultural

collapse. Records of warfare, often timed to specific astronomical events,

came to an end at about the same time, as did chronicles of their kings

and queens.

After the Classic Maya collapse in the ninth century, written records

appear primarily in painted books called codices. Codices are made from

tree bark that has been flattened, covered with a lime plaster and folded

accordion-style. They are usually painted on both sides.

Only a very few of these screenfold books survive today, all dating

to the Postclassic period (A.D. 900-1541). They record almanacs focusing

on astronomy, agricultural cycles and weather patterns. The rain god

Chak is represented 134 times in the almanacs of the Dresden Codex,

while many other gods appear only once or twice.

The Dresden Codex traces a sequence of 584-day periods, documenting

Venus in relation to seasonal cycles of the sun and moon. Another almanac

in this codex shows the planet Mars as a "rain beast" connected

with the 780-day Mars cycle.

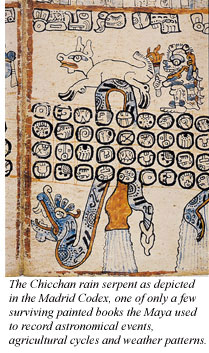

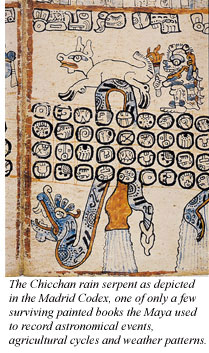

The Madrid Codex represents a 260-day planting cycle controlled by the

Chicchan "rain serpent," whose rattle tail represents the

constellation Pleiades. In the Madrid sequence, the disappearance of

the serpent's rattle coincides with the disappearance of the Pleiades

from view in May at the onset of the rainy season. The Yucatac Maya

still call the Pleiades "the rattlesnake's rattle" (tzab).

Detailed records of the Maya calendar and astronomical cycles allow

me to pose another question. Did the Maya have knowledge of longer astronomical

cycles related to climate change?

The answer seems to be no, although we do not yet understand all of

the Maya records.

The Maya were expert "naked-eye" astronomers, and they had

a continuous cultural tradition extending back to the time of Christ.

No almanacs have survived from this period, but some records of the

seventh and eighth centuries appear in a 13th-century codex.

The Maya had a complex series of calendars recording time cycles of

great length. One such cycle is the 52-year Calendar Round, synchronizing

their 260-day religious calendar with a 365-day calendar based on the

solar year. Two cycles of the Calendar Round (104 years) were used to

record a great Venus Round. This involved a Venus almanac of 5 Venus

cycles coordinated with the cycles of the sun and the moon over a period

of 8 years. This Venus almanac (5 x 584 days = 8 x 365) was repeated

13 times so that all three astronomical cycles would realign with the

260-day divination calendar after 65 Venus cycles. Doubling this cycle

we have a cycle of 208 years - which, oddly enough, fits rather neatly

with the solar forcing cycle.

Although this must be a coincidence, it seems likely that after more

than a millennium of observation, the Maya did develop some records

of long climate cycles. Watching for the rains to come in May each year

must go back to the dawn of Maya civilization.

Susan Milbrath

is Curator of Latin American Art and Archaeology at the Florida Museum

of Natural History and Affiliate Professor of Anthropology at the University

of Florida. She is the author of Star Gods of the Maya: Astronomy

in Art, Folklore, and Calendars.

Mayan

Meltdown

Mayan

Meltdown

The

team, part of UF's new Land Use and Environmental Change Institute,

could easily see the strata of white gypsum segmenting the core like

icing between layers in a chocolate cake, but only the sensitivity

of the core logger could map those layers with the precision the three

University of Florida geologists needed to resolve their questions

about climate conditions around Lake Chichancanab during the last

three millennia.

The

team, part of UF's new Land Use and Environmental Change Institute,

could easily see the strata of white gypsum segmenting the core like

icing between layers in a chocolate cake, but only the sensitivity

of the core logger could map those layers with the precision the three

University of Florida geologists needed to resolve their questions

about climate conditions around Lake Chichancanab during the last

three millennia. But

although the scientists were able to identify dry periods from the

1993 samples, the cores and the technology to study them lacked detail.

But

although the scientists were able to identify dry periods from the

1993 samples, the cores and the technology to study them lacked detail. "With

these new cores and the high-resolution density records we generated,

we were able to detect cycles in the record," Hodell says.

"With

these new cores and the high-resolution density records we generated,

we were able to detect cycles in the record," Hodell says. Maya

Perspective

Maya

Perspective