Explore Magazine

Volume 6 Issue 2

CELLULOSE

Hero

CELLULOSE

Hero

UF Entomologist

Nan-Yao Su Rescues National Landmarks from Termites

by Chuck Woods

It

sounds like one of those old horror movies:

rampaging monsters, panicking

residents, crumbling

landmarks - and scientists scrambling for

ways to stop the destruction.

But unlike those fictional monsters, Formosan "super termites"

and their milder cousins are for real - gnawing their way through some

of the nation's most famous landmarks.

About two or three times more destructive than a regular subterranean

termite, the Formosan termite is as much a natural disaster as a hurricane

or tornado. But instead of warning residents with howling winds or pounding

rain, it usually goes unnoticed until the damage is done.

Worse yet, the termite has been a wily target, surviving a barrage of

pesticides and other control measures by folks who knew little about its

nesting and foraging habits.

Nationwide, annual damage estimates for termites range as high as $3 billion.

In Florida, the Formosan termite was first identified in Miami-Dade and

Broward counties in 1980. The pest is now well established along the southeast

Florida coast as far north as Martin and St. Lucie counties. In 1985,

colonies were found in Orange and Escambia counties. And the pest showed

up in Hillsborough County in 1991.

New outbreaks - mainly caused by people moving infested materials - are

spreading the pest throughout the Southeast. Unlike other native subterranean

termites, which have been found as far north as Toronto, the Formosan

termite prefers warmer climates where colony populations average several

million.

"If we don't step

up our control measures, the Formosan termite could become firmly established

throughout the state, probably within 20 or 30 years," says Nan-Yao

Su, professor of entomology with UF's Institute of Food and Agricultural

Sciences.

The

Big Easy

"The problem in some Florida communities could eventually become

like the one in New Orleans where more than 90 percent of the buildings

in the French Quarter now are infested with Formosan termites," Su

says.

When every known control measure failed to stop the pest in the Presbytere

and Cabildo in the Big Easy, the National Park Service, which oversees

these and other national treasures, called Su for help.

Mark Gilberg, research coordinator for the park service's National Center

for Preservation Technology and Training in Natchitoches, La., learned

about Su's breakthrough research on termites at an international conference

in Yokohama, Japan.

"At the 1990 conference, Dr. Su presented his research findings on

using a chemical called hexaflumuron and his revolutionary new baiting

system to control the pests," Gilberg says. "When I began coordinating

research for the park service in 1993, we awarded a grant to Su to explore

the use of his baiting technology to control termites in our historic

buildings and structures."

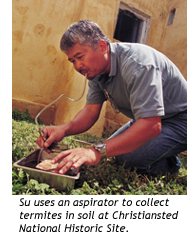

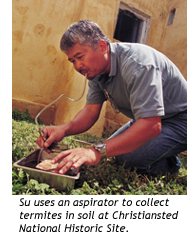

Since then, Su has used the new baiting system at several park service

sites, including the French Quarter properties, the Christiansted National

Historic Site in St. Croix, the Statue of Liberty in New York, the San

Juan Historical Landmark in Puerto Rico and the Kingsley Plantation on

Fort George Island near Jacksonville, Fla.

"In all cases, Su's new termite control system brought Formosan and

other subterranean termites under control for the first time, further

enhancing his reputation as one of the world's leading termite experts,"

Gilberg says. "Everyone in the national historical preservation community

knows his name."

Su's technology is ideal for protecting historic properties because there's

no need to drill holes through floors, walls or any other fabric of the

structure to introduce pesticides.

Gilberg says conventional pesticide sprays did not stop the highly destructive

Formosan termite in the French Quarter, but Su's control system brought

the pest under control for the first time by destroying its underground

colonies.

Su, based at UF's Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, says

his system is effective because termites spread the hexaflumuron pesticide

bait themselves.

"Conventional pesticide treatments may keep subterranean termites

out of buildings, but they don't control termite colonies in the ground,"

Su says. "Unlike traditional barrier-control methods, our new system

eliminates underground colonies, which is the key to controlling termites."

"Conventional pesticide treatments may keep subterranean termites

out of buildings, but they don't control termite colonies in the ground,"

Su says. "Unlike traditional barrier-control methods, our new system

eliminates underground colonies, which is the key to controlling termites."

Hexaflumuron is a growth regulator that prevents termites from molting,

thereby reducing the ability of the worker population to sustain the colony.

The chemical has a low toxicity to humans and the environment, and less

than 1 gram kills an entire colony containing millions of termites.

To deliver the growth regulator, Su developed a small monitoring and feeding

station placed in the ground near buildings. When termite activity is

detected, the monitoring devices are replaced with a cellulose material

laced with the insect growth regulator. Once the colony has been eliminated,

the system remains in place to detect any future termite activity.

St.

Croix Siege

Most recently, Su helped rescue a 250-year-old Danish fort that was under

siege by subterranean termites in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands.

Joel Tutein, superintendent for the park service in St. Croix, says termites

have been the single most destructive force to hit the fort, which was

built between 1739 and 1749 when the island was colonized by Denmark.

Now one of the island's most popular tourist sites, the fort attracts

nearly 100,000 visitors annually.

"The fort has been through hurricanes, floods, earthquakes and occupations,

but nothing has been more destructive than subterranean termites,"

Tutein says. "If we did not solve the termite problem, we would have

watched the entire structure crumble before our eyes."

Things started to get expensive in the 1980s, when termite-infested pine

and tropical hardwood had to be replaced every five or six years.

"We tried every available chemical and treatment, including tenting

and drilling pesticides into walls, but nothing seemed to work,"

Tutein said. "It was really frustrating because we were spending

money on the same repair projects over and over again."

The problem reached crisis three years ago when the park service wanted

to start a long-overdue $750,000 restoration project.

"We could not begin a major renovation program at the fort until

we found a way to stop the termites," Tutein said. "Otherwise,

wooden beams, floors, doors and shutters would have to be replaced every

few years at enormous cost."

Zandy Hillis-Starr, chief of natural resources for the National Park Service

in St. Croix, worked on the project with Su and his assistant, Paul Ban.

Hillis-Starr believes termites at the fort are under control for the first

time.

"When we started on this project, I was not very optimistic the pest

could be controlled because of all the disappointments we're had over

the years," Hillis-Starr says. "But now I feel comfortable that

we will not have to deal with this problem again for at least 20 years.

If we do have a problem, UF will be back to help."

During

the initial phase of the project, which lasted about two years, the three

partners - Su, Ban and Hillis-Starr - located the sources of termite infestations

at the fort. Then they installed Su's new baiting system to monitor and

control the pest. The historic site now is protected by 40 monitoring

stations, and no activity has been detected for more than 12 months.

During

the initial phase of the project, which lasted about two years, the three

partners - Su, Ban and Hillis-Starr - located the sources of termite infestations

at the fort. Then they installed Su's new baiting system to monitor and

control the pest. The historic site now is protected by 40 monitoring

stations, and no activity has been detected for more than 12 months.

"It's safe to say all underground termite colonies around the fort

are gone," Su says. "During the height of the infestation, there

probably were 20 to 30 underground termite colonies with millions of termites

attacking the fort, building tubes up through floors, walls and other

wood structures."

The park service estimates the termite eradication program will save up

to $700,000 in repair costs over 20 years.

Su identified the termite as the Heterotermes species, which is common

in the Caribbean, Central America and some South American countries. He

said it's less aggressive than the native subterranean termite in Florida

and less destructive than the Formosan termite.

"Because there were many infestations in walls, ceilings and other

wood structures that contained live termites, we also placed a small plastic

bag containing bait directly over these active infestations," he

said. "In addition to the underground bait stations, our aboveground

monitoring and bait stations have been very helpful in controlling termites."

Lady

Liberty

For most of its 115 years watching over New York Harbor, the Statue of

Liberty has been isolated from termites by several hundred yards of water.

But by 1994, the statue's museum area was so infested with swarming termites

that the National Park Service had to temporarily close the area to the

public.

"It was the first time in more than 100 years that there was any

problem with these termites on Liberty Island," Su says. "I

suspect they found their way to the island when the statue was being restored

for the 1986 Centennial celebration. They probably hitchhiked in with

landscaping plants and wood construction materials."

The most severe infestations were in the base of the monument, which houses

the museum and utility rooms.

"We had some serious termite infestations in the museum's wooden

display cases, which contained valuable artifacts and historical documents,

but none of these national treasures were damaged," Su said. "At

no time did the termites pose any threat to the structural integrity of

the monument - they were not about to topple Lady Liberty."

To control termites munching on the wooden display cases in the museum,

Su developed an aboveground feeding station that delivers bait on-site

immediately. At the same time, Su's underground baiting system eliminated

the problem of flying termites in less than one year.

Similar success stories in controlling subterranean termites have been

documented at park service sites in San Juan and Fort George Island near

Jacksonville.Moreover, Su's system is being used by millions of residents

and businesses around the state and nation.

The system, to which

UF holds the patent, is licensed to Dow AgroSciences and marketed worldwide

as the Sentricon Termite Colony Elimination System.

Last year, Su and Dow AgroSciences received the Presidential Green Chemistry

Challenge Award from the Environmental Protection Agency for developing

the Sentricon system. The award recognizes technical innovation that incorporates

the principles of "green chemistry" into pest control design,

manufacturing and use.

In 1995, Su was honored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for his

breakthrough technology, which was described as "the most important

advance in termite control in more than 50 years."

Nan-Yao Su

Professor, Department of Entomology

(954) 577-6339

nysu@ufl.edu

"Conventional pesticide treatments may keep subterranean termites

out of buildings, but they don't control termite colonies in the ground,"

Su says. "Unlike traditional barrier-control methods, our new system

eliminates underground colonies, which is the key to controlling termites."

"Conventional pesticide treatments may keep subterranean termites

out of buildings, but they don't control termite colonies in the ground,"

Su says. "Unlike traditional barrier-control methods, our new system

eliminates underground colonies, which is the key to controlling termites." CELLULOSE

Hero

CELLULOSE

Hero During

the initial phase of the project, which lasted about two years, the three

partners - Su, Ban and Hillis-Starr - located the sources of termite infestations

at the fort. Then they installed Su's new baiting system to monitor and

control the pest. The historic site now is protected by 40 monitoring

stations, and no activity has been detected for more than 12 months.

During

the initial phase of the project, which lasted about two years, the three

partners - Su, Ban and Hillis-Starr - located the sources of termite infestations

at the fort. Then they installed Su's new baiting system to monitor and

control the pest. The historic site now is protected by 40 monitoring

stations, and no activity has been detected for more than 12 months.