UF RESEARCHERS CONTRIBUTE THEIR

EXPERTISE TO THE NATIONAL BATTLE

AGAINST TERRORISMBy Joseph Kays

THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IS RESPONDING ON NUMEROUS FRONTS, OFFERING ITS EXPERTISE IN SUCH AREAS AS ENGINEERING, BIOTERROR AND MONEY LAUNDERING. THIS SPECIAL REPORT LOOKS AT SOME OF THE WAYS IN WHICH UF IS RESPONDING TO THE NATIONAL CRISIS.

When UF civil and coastal engineering Professor David Bloomquist saw the World Trade Center towers collapse on September 11, he realized the area around ground zero would closely resemble the site of a major earthquake.

"When the World Trade Center towers collapsed, some seismographs actually picked it up as if it were an earthquake," says Bloomquist.

And assessing earthquake damage is one of several applications of the laser mapping technology University of Florida researchers have been refining for the last six years.

"The attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon not only created a human tragedy but they caused massive infra-structural devastation as well," Bloomquist noted in an emergency grant proposal to the National Science Foundation. "Besides the hundreds of thousands of tons of debris, several surrounding buildings near ground zero were not thought to be structurally salvable, and there was concern that several were slowly deteriorating."

Using the $45,000 NSF grant, UF researchers teamed up with colleagues from several federal agencies and Optech Inc., the Canada-based laser manufacturer. Just 12 days after the attack, the team was digitally mapping southern Manhattan from the ground and from the air.

On Sept. 23, 3,800 feet above lower Manhattan, in airspace still closed to commercial traffic, a Cessna Citation jet on loan from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration bounced 33,000 laser pulses a second off buildings and remnants of buildings from the Hudson River to the East River, gathering hundreds of millions of pieces of data to be used in assessing their structural integrity.

Down in the concrete canyons around the 16-acre World Trade Center site, technicians from Optech used the company's state-of-the-art ILRIS-3D Lidar Imaging System to gather similar data from the tower site and adjacent buildings.

Within hours of the initial data collection, UF research coordinator Michael Sartori was crunching the numbers in his hotel room, a job he says takes an average of 39 hours for every hour of collection time and that he expects to continue for several months.

Generating even a small sample of data points using traditional surveying techniques to assess the overall condition of a damaged building is extremely time-consuming, Bloomquist says.

Instead, the UF/Optech team is employing both airborne laser swath mapping, or ALSM, and ground-based scanning laser technology to collect and analyze hundreds of millions of laser range measurements of the World Trade Center and Pentagon sites. The measurements are accurate to within 3 centimeters.

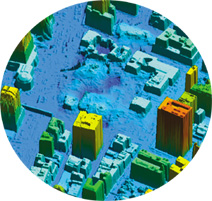

While the result looks like a grainy photograph, it is actually a "cloud" of laser data points, each with its own unique X, Y and Z coordinates.

"Once captured and processed, this data can be used to monitor movement of walls, both interior and exterior," Bloomquist says.

The combined air- and ground-based observations are being used to create three-dimensional models of the disaster sites far more detailed and accurate than has ever before been available to recovery workers and planners, Bloomquist says.

UF was the first academic institution in the United States to buy and operate an ALSM unit. Ramesh Shrestha, director of UF's recently established GeoSensing Engineering and Coastal Mapping Research Center for Natural Disasters and Geo-Surficial Processes, has procured more than 28 research projects using the technology, funded by federal, state and local agencies.

These include landslide detection and monitoring, sinkhole assessment, coastal effects from hurricane damage and cratering from artillery bombardment.

Ground-based scanning laser technology produced this image of the area of the Pentagon where the hijacked plane struck. While engineers have surveyed the adjacent buildings for structural integrity, the potential for additional damage exists, Bloomquist says.

"By comparing pre data with post data, the laser allows you to compute the change in position of a building within an inch of movement," he says. "This large a shock to the foundation could damage some of the pilings that buildings are set on. We can look at a wall and determine if it's still vertical, and, if not, how many degrees it is off of vertical."

That's why the researchers intend to go back to New York in the near future to conduct a follow-up survey.

Bloomquist says one of the engineering lessons of the World Trade Center collapse is the value of pre-damage laser models. The ability to recognize damage is much greater when pre- and post-event data can be compared, he says.

"The destruction in New York City, while unimaginable, occurred over only 16 acres of area," Bloomquist says. "If, probably when, a major earthquake strikes a metropolitan area like Los Angeles or San Francisco, this level of damage most likely would affect several square miles of area. Hence, future research using this technology to log detailed data of pre-earthquake structures would be very helpful for rescuers and engineers in damage assessment."

While laser mapping the World Trade Center and Pentagon sites may offer more comprehensive assessment of the damage done there, the greatest benefit of the exercise lies in showcasing the potential of this new technology, Bloomquist says.

"There's a lot of interest in getting this technology out in front of people," says Sartori.

"If we get the technology out there," Bloomquist adds, "people will develop applications for it."

Like modeling the impact of different levels of hurricanes on evacuation routes.

"Typically, the topographical maps used in developing hurricane evacuation routes have five-foot contours," Sartori says of a project UF is discussing with the Federal Emergency Management Agency. "With our higher-resolution maps of coastal regions, we can more accurately determine what level of storm surge will wash out which evacuation routes, and that's important data for emergency planners to have."

The group also has a grant from the Florida Department of Transportation to employ ALSM to provide early detection of sinkholes along the state's major highways. At the centimeter-level resolution that the system provides, emerging sinkholes appear like craters on the moon. And filtering techniques the team has developed make it possible to spot these craters even if they are covered by vegetation. Basically, we tell the computer to disregard any data above ground level, so we can see potential hotspots even if they occur in heavy overgrowth.

"As a geotechnical engineer, this ability to combine accurate surficial geometry with subsurface exploration greatly enhances our predictive capabilities in assessing sinkhole damage," Bloomquist says.David Bloomquist

Associate Professor, Department of Civil and Coastal Engineering

(352) 392-0914

dave@ce.ufl.eduRelated web site:

http://www.alsm.ufl.edu

Heather Walsh-Haney has seen plenty of death while pursuing a doctorate in forensic anthropology at the University of Florida. As the senior graduate student at UF’s Maples Center for Forensic Medicine, Walsh-Haney has overseen hundreds of death cases in the center’s state-of-the-art laboratory.

In 1996, she accompanied the late William R. Maples, a renowned forensic anthropologist,

to the site of the ValuJet plane crash in the Florida Everglades to help identify the victims.But nothing could have prepared her for the scale of human devastation wrought by the collapse of the World Trade Center on September 11. Anthropology doctoral student Heather Walsh-Haney and Associate Professor Michael Warren with a colleague from the Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team at the Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island, N.Y., where they spent two weeks helping to search for remains from the World Trade Center attacks. Since forensic anthropologists are trained to identify human remains and differentiate between trauma that happened during life, at the time of death, or long after death, they are often deployed following a mass fatality as part of the Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team (DMORT) program of the U. S. Public Health Service.

Walsh-Haney was attending a meeting with Anthony Falsetti, co-director of the Maples Center, when news of the World Trade Center attacks reached them.

“As we watched the collapse of the towers, it quickly became apparent that DMORT teams would likely be deployed and that Drs. Falsetti and (Michael) Warren and I might be called to New York City.”

At 6:30 that night, Walsh-Haney’s DMORT team leader contacted her and asked if she would be able to come to New York City for a minimum two-week deployment.

“I agreed to go and immediately started thinking about what responsibilities (family, school and work) could be put on hold,” Walsh-Haney says. “My husband rushed out to pick up a canteen, knife and other equipment required by DMORT while I stayed home to pack additional field gear I thought might be useful, including a laptop computer, field manual, calipers, camera, film, dental probes and hand lens.”

At 6 a.m. on September 12, Falsetti, Warren and Walsh-Haney headed north on Interstate 95, driving straight through to Stewart Air Force Base about 60 miles north of New York City.

For the next few days, the forensics experts waited while city officials, including firefighters and police officers, tried to deal with a disaster that had also taken hundreds of their colleagues.

“I spent my time getting ready for meetings, walking downtown and taking in the makeshift shrines and missing persons flyers,” Walsh-Haney says.

Initially, Walsh-Haney was assigned administrative duties at the DMORT command center, and while she recognized the importance of this work, she admits she was anxious to employ her skills in a scientific capacity.

That opportunity came the next day, when Walsh-Haney and Warren were deployed to help separate human remains at the Staten Island Fresh Kills Landfill, where most of the debris from ground zero was taken by barge.

“Green army tents, a few trailers and dozens of bulldozers, cranes and huge trucks were on top of the landfill, while military helicopters circled and secured the airspace above,” she recalls.

The most vivid memory Walsh-Haney has of the landfill is of a huge American flag waving over the green army tents.

Walsh-Haney says the flag, which survived the assault on the towers to later fly at the 2002 Superbowl and Winter Olympics, inspired the workers sifting through the enormous amounts of rubble gathered from ground gero and brought to the landfill for processing.

“I learned that I could handle that travesty emotionally; I could handle the pressure,” Walsh-Haney says. “And I was proud to help the nation.”

Personnel from many state and federal agencies searched the rubble using rakes and shovels, bringing all organic material to the forensics experts.

“A decision was made to rely almost completely on DNA to determine the identity of the dead,” says Warren. “Our primary role was to examine all of the organic material and determine whether or not the tissue was human or non-human. Non-human remains would simply prolong the identification process and unnecessarily add to the tremendous expense of DNA testing.”

Meanwhile, Falsetti, one of the nation’s premier forensic anthropologists, was assigned to ground zero.

“My first impression was like many others. I simply couldn’t believe it,” he says. “When we arrived the fire was still burning fiercely and smoke was billowing out of lower Manhattan.”

Falsetti was part of a seven-member team that included a forensic pathologist, three body trackers and two evidence technicians.

“My mission was to examine all remains and make a tentative identification as to whether they represented a member of the NYPD, FDNY or Port Authority,” he says.

Working 12-hour shifts daily for two weeks on top of the landfill, Walsh-Haney says “the greatest challenge was making sure that fatigue did not add to the emotional challenge I was already under. The scale of the disaster was emotionally taxing, but those emotions have to be put in check while working. Otherwise I would have been unable to use my skills to help.”

Heather Walsh-Haney

Doctoral Candidate, Department of Anthropology

(352) 846-1579

ufav8r1@ufl.eduAnthony Falsetti

Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology

(352) 392-6772

falsetti@ufl.eduRelated web site:

http://maples-center.ufl.eduby Joseph Kays

An indoor air cleaning system originally developed to zap dust mites and mold spores also destroys airborne anthrax and other pathogenic microbes, says the University of Florida engineering professor who pioneered the technology.

The system has been successfully tested against a close cousin of the anthrax bacteria and could be installed relatively inexpensively and quickly in office and home heating and air conditioning systems, says Yogi Goswami, a UF professor of mechanical engineering and director of UF’s Solar Energy and Energy Conversion Laboratory.

“There are other technologies for air cleaning, but for air disinfection, there is no more effective system,” Goswami says.

The photocatalytic air cleaning system relies on the interaction between light and titanium dioxide, a simple and widely available chemical. When light is absorbed into the titanium dioxide, it acts as a catalyst to produce an oxidizing agent.

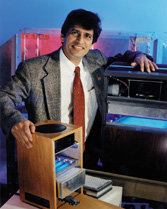

D. Yogi GoswamiThe agent, called a hydroxyl radical, “is like a bullet for the bacteria,” Goswami says, destroying dust mites, mold spores and pathogens by disrupting or disintegrating their DNA.

Goswami came up with the system in the mid-1990s as a cure for so-called “sick building syndrome,” when poor ventilation and a build-up of mold or mildew cause illnesses for people who work inside. Initial research proved that the system kills the mold spore, aspergillus niger, considered to be one of nature’s hardiest spores, he said.

More recent research has shown that the system also destroys bacillus subtilis, a spore that causes food spoilage and is a cousin of the anthrax spore, bacillus anthracis.

“In the laboratory, we normally test with nonpathogenic bacteria that are closely related to pathogenic bacteria, so there’s no risk to people,” Goswami says. “As we expected, our tests showed the system was effective against bacillus subtilis.”

The technology is an improvement over traditional filter-based systems in part because there is no opportunity for bacteria to collect and multiply on the filters that clear it from the air, he says.

“Filters can actually increase the danger because they concentrate the bacteria,” he says. The system is also an improvement over systems that use ultraviolet light, which do not consistently kill all the bacteria, he adds.

Goswami says the technology could be installed in central ventilation systems to decontaminate buildings or homes, or used in specific locations where contamination is feared. Given the incidents of anthrax contamination within the U.S. Postal Service, one application would be to install it in mail sorting or collection areas, he says.

“This is affordable for people. A central system for a single-family house would probably be in the range of $1,000 to $1,500,” he estimates.

As part of UF’s technology-transfer mission, the technology was patented and licensed to a Gainesville-based company, Universal Air Technologies. The company, which got its start at UF’s biotech incubator, the Biotechnology Development Institute in Alachua, Fla., sells a variety of portable and central air purification systems based on the technology.

by Aaron Hoover

D. Yogi Goswami

Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering

(352) 392-0812

solar@cimar.me.ufl.edu

Hoy, a professor of entomology in UF’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences who serves on a National Academy of Sciences Committee on Biological Threats to Agricultural Plants and Animals, maintains that U.S. borders are vulnerable to theUF entomology Professor Marjorie Hoy examines a citrus tree attacked by an invasive insect called the Asian citrus psylla. smuggling of bacteria, viruses and insects that could be used to attack agricultural targets.

Every day, destructive organisms are brought into the country at airports, seaports and land borders. Those same pathways could be used for intentional attacks,” said Hoy, whose research involves the biological control of invasive insects in Florida citrus.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), some of the country’s high-risk pathways are Miami, Los Angeles and New York, where the majority of the nation’s visitors and commercial shipments enter the country.

Hoy says Florida is particularly vulnerable because of the large number of visitors to the state. Florida had more than 11 million international air passenger arrivals in 1999, almost one-fifth of the U.S. total, according to the USDA. Moreover, one-third of imported produce and plants enter the United States through Miami.

Major U.S. airports such as Miami’s are guarded by the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, the agency responsible for protecting the nation’s crops and livestock from invasive organisms.

The agency intercepted 1.8 million illegal plants and animals in 1999, of which more than 52,000 were threats to U.S. agriculture or the environment.

While that may sound like a lot of seizures, statistics show the agency inspects only 2 percent of inbound shipments and travelers. Hoy says such weaknesses in the system increase the probability that agricultural bioterror threats could enter the country undetected.

“We need a more efficient inspection system,” Hoy says. “Officers who inspect cargo and passengers are overwhelmed.”

The increasing volume of cargo and passengers is making a tough problem much more difficult. In addition to traditional shipments and passengers, Hoy says, international mail is another high-risk pathway for bioterrorism.

In Miami, for instance, 10 million international mail packages arrived in 2000. Of those, 14,500 packages — less than 0.2 percent — were inspected. In the inspected packages, agents found 1,017 actionable threats to U.S. agriculture, according to the USDA.

Threats ranged from Mediterranean fruit flies, which caused an outbreak in Florida in 1997 that cost the state $32 million to eradicate, to citrus canker bacteria,

which has cost $170 million to fight since 1994.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Beagle Brigade is a group of nonaggressive detector dogs and their human partners who search travelers' luggage for prohibited fruits, plants and meat that could harbor harmful plant and animal pests and diseases. These detector dogs work with inspectors and x-ray technology to prevent the entry of prohibited agricultural items. A Cornell University report estimates that invasive insects, animals, plants and microbes — all termed “pests” by scientists — cost the United States $123 billion a year.

Other biological threats to agriculture that concern officials are foot-and-mouth disease, hog cholera, tick-borne heartwater disease from the Caribbean, fruit flies and many other disease-bearing insects and parasites.Other biological threats to agriculture that concern officials are foot-and-mouth disease, hog cholera, tick-borne heartwater disease from the Caribbean, fruit flies and many other disease-bearing insects and parasites.

Hoy’s job is to anticipate and defend against insect threats to Florida citrus.

She says that by developing solutions for current problems with smuggling or accidental introductions of pests, the nation is preparing for intentional attacks.

“From a scientific standpoint, these problems are two sides of the same coin,” she says. “Whether it’s intentional or accidental, most scientific responses would be similar.”

Hoy and other researchers use several methods of controlling insects.

One method involves breeding sterile insects that mate with the target insect, thereby reducing its chances of reproducing. Another increases the population of natural predators to destroy the target insect. A third method introduces a parasitoid from the target insect’s home country. A parasitoid is an insect that lays its eggs inside the target insect, thereby destroying the host.

For researchers such as Hoy, the challenge is having a control plan in place before invasive pests arrive, regardless of how they arrive.

“Our borders will never be 100 percent secure,” Hoy says. “But we can and must do better.”Marjorie Hoy

Eminent Scholar, Department of Entomology and Nematology

(352) 392-1901 x153

mahoy@gnv.ifas.ufl.edu

by Paul Kimpel

Fletcher Baldwin has spent much of his career studying how organized crime uses the international financial system to launder and distribute money, and he says terrorists are just organized criminals with a twist.

“Organized crime and organized terrorists have common characteristics and similar goals,” says Baldwin. “The U.S. and other victim states can learn from those commonalities and goals, and can react accordingly.”

The United States began reacting immediately to the September 11 attacks. In concert with the military response, Congress passed and on October 26 President Bush signed the USA Patriot Act. Baldwin says that although many of the information-gathering provisions of the Patriot Act had been on the FBI’s “wish list” for years, elected officials hesitated to implement them because civil libertarians and other groups opposed the provisions.

“It is extremely regrettable that it took September 11 to create the heightened level of political awareness needed to recognize the dangerous nature of the relationship between money laundering, terrorism and technology,” Baldwin says. “Now we have organized transnational political will with an attitude, and that will continue as long as terrorists are operating at their current level.”

Baldwin says the United States has taken the same approach toward the enforcement of international financial law that it has taken in its military war on terrorism: either you’re with us or you’re against us.

“U.S. authorities have told foreign banks that either they freeze the assets of suspicious clients or they won’t do business in the United States again,” he says.

Complicating matters, however, is that fact that much of the illicit money rests in our own vaults and those of some of our closest allies, particularly the members of the G-7, which includes the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, Japan and Russia.

“Al Qaeda moves its money through a network of underregulated banks, and then when the source of the money is sufficiently disguised, moves it into safer, more stable financial institutions,” Baldwin says. “After the terrorists route their money through these underregulated systems, often in accounts registered to shell companies or legitimate businesses, or in banks with little or no oversight, the money appears to be clean.”

While terrorists have taken advantage of the growth in electronic commerce and the Internet to facilitate their plans, Baldwin believes technology is helping law enforcement pursue the terrorists more than most people realize.

“You and I will be the last ones to know about new surveillance technology,” he says. “I believe we already have technologies that will allow law enforcement to determine if virtually any bank, worldwide, has fluctuations in its money flow that would raise suspicions.”

Baldwin has lectured about complicated international financial law from an academic standpoint for years, but since September 11 he says conference participants — like those at a Conference on Money Laundering, Cybercrime and International Financial Crimes that he helped organize in Miami in January and at another one hosted by UF in early March — want experts like him to cut to the chase, especially about the Patriot Act.

“We are taking a much more practical approach to explaining how the USA Patriot Act affects the banking and law enforcement communities,” Baldwin says. “They want and need to understand the content and application of the law. In the past, if a bank didn’t adhere to the ‘know your customer’ principle or didn’t file a suspicious activities report, nothing much would happen. Now, there is a real sense of urgency. Banks and companion institutions, along with myriad federal agencies, are on the front lines as far as sharing information, as well as detecting and seizing illicit funds or, for that matter, lawful funds destined for illicit enterprises.”

Baldwin says the rapidity with which the lengthy Patriot Act moved through Congress left a lot of loose ends that will have to be sorted out in the courts. Many of these involve balancing or preventing infringement of individual freedoms.

“Although the Patriot Act incorporates many appropriate anti-terrorism provisions, such as strengthening wire-tap capabilities, identification procedures when dealing with suspected terrorists and information sharing,” Baldwin says, “other provisions of the act are overly broad and are candidates for constitutional debate and judicial review.”Fletcher N. Baldwin Jr.

Professor, College of Law

(352) 392-2211

baldwinfn@law.ufl.eduRelated web site: http://www.law.ufl.edu/cifcs/