Best Known As A Writer,

Zora Neale Hurston Was Years

Ahead Of Her Time As An Anthropologist

By Irma McClaurin

And our understanding of her motivations and methods might have died with her, lost forever to a pile of ashes.

Like an urban legend, there are many versions of the story about Hurston's last days and the fate of her belongings, but all revolve around a local official, possibly a sheriff's deputy, coming upon them being burned outside an apartment or welfare home in St. Lucie County.

We may never know what it was about the odd assortment of a destitute woman's belongings that caught his eye, and moved him to retrieve them from the bonfire. But the bounty of his quick intervention forms the core of the Zora Neale Hurston Collection of the George A. Smathers Library at the University of Florida.

It is these singed manuscript pages, postcards, photographs, correspondence with fellow Black artists and intellectuals that guide me in my quest to understand Hurston and her place in American anthropology.

Zora Neale Hurston's was an elusive life, despite the scores of manuscript pages, letters and photos she left behind, not to mention the volumes of essays, critical studies and biographies they have spawned. But there is a story in these archives, a life behind the words neatly written or typed on the manuscript pages, a mystery revealed.

The Collection

The University of Florida is one of four major repositories of archives by and about Zora Neale Hurston. Thousands of pages of material have been catalogued - including correspondence, original copies of manuscripts, published articles, biographical and critical papers, and photographs - all waiting to provide clues about the public and private life of this notable writer and anthropologist.

The library received the nucleus of its collection in 1961, with other materials donated in 1960, 1971 and 1979. Like the archives of the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, the Beinecke Library at Yale and the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University, those at UF have become a magnet for researchers from around the world who seek insight into the life of Zora Neale Hurston. Most come in search of the literary Zora; I seek to understand her as an anthropologist who preserved and analyzed Black folk culture.Giving Zora Her Due

UF's Department of Anthropology recognizes that Zora Neale Hurston left a significant anthropological legacy. Embedded in her short stories, plays and even her reports for the Federal Writers Project are an abundance of details about Black folk culture in the South that build upon her ethnographic training and detailed fieldwork.

In 1998, the department established the Zora Neale Hurston Diaspora Studies Project, which seeks to encourage research about the Diaspora experience in Florida and its links to other Diaspora communities in the world. A pilot program, the Zora Neale Hurston Ethnographic Field School, was launched in Summer 1999 in the Central American country of Belize. The aim was to train students in ethnographic field methods as they conducted their research.

Another achievement for the department is the Zora Neale Hurston Scholarship, a three-year graduate fellowship begun with an $18.75 contribution from Hurston's brother. Since its modest beginnings, the fellowship has had many generous benefactors and continues to seek contributions that will expand the number of ZNH scholars, support research on the African Diaspora in Florida and make the ZNH Field School a permanent fixture.

Hurston's research was deeply rooted in a Diaspora paradigm, which stressed an examination of the cultural continuities and differences that emerged when Blacks were scattered across the Americas and Europe as a consequence of slavery. Hurston followed the scattering, traveling to the Bahamas, Honduras, Jamaica and throughout most of the southern United States to collect folklore. She also published one detailed description of everyday life and rituals in Jamaica and Haiti, Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica. True to form as an anthropologist, and vintage Zora, Hurston became a voodoo priestess initiate while conducting her research for that book.

Woman Behind The Archives

Pulitzer Prize-winning American literary scholar Leon Edel has suggested that trying to write a biography is akin to trying to discern the muted pattern in a carpet. For my current research I have chosen to focus on a very short span of Hurston's life - those few years in which she conducted the fieldwork that ultimately became Mules and Men, her 1935 collection of African-American folklore gleaned from her travels in the South. Drawing primarily on Hurston's correspondence with poet Langston Hughes about her theories on Black folk culture, I hope to produce a unique portrait of Zora Neale Hurston as an important innovator in anthropological theory and method. Such a highly focused work will also seek to reinstate her in the annals of the history of American anthropology.

The funding for this initial research came from two sources: a UF College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Humanities Enhancement Grant and a Donald C. Gallup Fellowship in American Literature through the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale.

A Bohemian of sorts, politically conservative, if not apolitical, Hurston was the kind of person who inspired extreme reactions: people either loved her or hated her. Fellow Harlem Renaissance writer Richard Bruce Nugent once remarked: "Zora would have been Zora even if she was an Eskimo."

At a period of time in American history when Black women worked mostly as domestics, shop clerks and, occasionally, teachers, Hurston earned her living as a writer and anthropologist. Indeed, though she took on numerous odd jobs, such as secretary to author Fannie Hurst, she also conducted scientific research for Franz Boas, considered by many to be the father of American anthropology.

Hurst once described Hurston as "an effervescent companion of no great profundities but dancing perceptions, ...(Zora) possessed humor, ... and what a fund of folklore!"

American anthropology was in its infancy in the early part of the century when Hurston was taking her training, and Boas not only emphasized intensive fieldwork in one place as a challenge to what he disparaged as "armchair" anthropology but also trained a cadre of (soon-to-be-famous) anthropologists, like Edward Sapir, Albert Kroeber and Margaret Mead. Zora Neale Hurston found herself among illustrious company under the tutelage of "Papa Boas."

Encouraged by Boas, Hurston gained confidence that her documentation and analysis of Black folk culture was important and necessary work.

"I was glad when somebody told me, 'You may go and collect Negro folk-lore.' In a way it would not be a new experience for me. When I pitched headforemost into the world, I landed in the crib of Negroism. From the earliest rocking of my cradle, I had known about the capers Brer Rabbit is apt to cut and what the Squinch Owl says from the house top. But it was fitting me like a tight chemise. I couldn't see it for wearing it," Hurston wrote in 1935 in the introduction to Mules and Men. "It was only when I was off in college, away from my native surroundings, that I could see myself like somebody else and stand off and look at my garment. Then I had to have the spy-glass of anthropology to look through at that."

Hurston embraced anthropology's belief that rigorous and systematic training provided its practitioners with a unique vision of the world. And her metaphor of anthropology as a "spy-glass," as an illuminating lens, still resonates today. But where she departed from convention was in her choice of subject matter. To study her own people as a "native anthropologist" ran counter to the prevailing intellectual winds. Further, her blurring of literary conventions with ethnographic data was a challenge of which she was keenly aware.

Hurston's willingness to go against the grain and to experiment with new ethnographic styles and methods positions her as the foremother of what is today called interpretive anthropology, or the new ethnography.

Despite Hurston's innovations in ethnographic writing and methodological strategies, despite her courageous conviction to position herself as a native anthropologist at a time when objectivist scientific approaches reigned, she is barely acknowledged as a force in the shaping and history of the discipline. While English departments have embraced her, most anthropology departments have ignored her.(Re) Inserting Zora

A great challenge for me as a scholar is to figure out how best to reinsert Zora Neale Hurston into the anthropological canon, and into the minds of the reading public. One of my goals is to promote her recognition as an innovator in theory and method who produced amazing ethnographic descriptions that were also reflected in her novels. I seek to have her books head the list of required readings in courses on the history of anthropological theory.

I have chosen to write about Hurston's life in a style reminiscent of her own, appealing to a popular audience rather than an academic one. This may be one reason why mainstream anthropologists have excluded Hurston from serious scholarly consideration, although feminist anthropologists have made her a symbol of the creative dynamism of feminist scholarship.

It is the life and career of a Bohemian that I seek to reveal, but the task is daunting. Her field notebooks are gone - perhaps burned in that irreverent bonfire, perhaps lost as she bounced around, from the citrus and railroad camps of Florida to the backwoods of Louisiana, always in search of "authentic" Negro culture. So I am left to comb files of manuscripts pages executed in a careful handwriting or meticulous typing and sift through a mélange of postcards and telegrams for insights into her methods for researching Black folk culture.

But, there is a mystery and charm to discovering Zora Neale Hurston. The inaccuracies that have surrounded her life add a bit of spice to a woman who proclaimed to the world: "I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow dammed up in my soul, or lurking behind my eyes."

It is this resiliency that has captured my attention, and that of countless other scholars who struggle to impose some order and meaning on the scorched remnants of her career in order to deepen our understanding of a woman who was creative, to be sure, but also complex beyond belief.Irma McClaurin

Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology

(352) 392-2253

mcclauri@anthro.ufl.eduRelated Web site:

http://web.uflib.ufl.edu/spec/manuscript/hurston/hurston.htm

American anthropology was in its infancy in the early part of the century when Hurston was taking her training under Franz Boas, considered by many to be the father of American anthropology. Boas emphasized intensive fieldwork in one place as a challenge to what he disparaged as "armchair" anthropology, and trained a cadre of famous anthropologists, like Edward Sapir, Albert Kroeber and Margaret Mead.

Encouraged by Boas, Hurston gained confidence that her documentation and analysis of Black folk culture was important and necessary work.

Zora Neale Hurston with migrant workers."When I pitched headforemost into the world, I landed in the crib of Negroism. From the earliest rocking of my cradle, I had known about the capers Brer Rabbit is apt to cut and what the Squinch Owl says from the house top. But it was fitting me like a tight chemise. I couldn't see it for wearing it. It was only when I was off in college, away from my native surroundings, that I could see myself like somebody else and stand off and look at my garment. Then I had to have the spy-glass of anthropology to look through at that."

- Zora Neale Hurston

Mules and Men, 1935

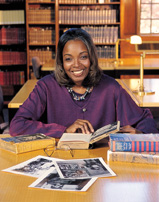

Irma McClaurin is an associate professor of anthropology and co-director of the Zora Neale Hurston African Diaspora Research Project at the University of Florida. She is the author of three books of poetry, and the ethnography Women of Belize: Gender and Change in Central America. Her edited book Black Feminist Anthropology: Theory, Politics, Praxis, and Poetics was published in September. She is currently working on a trade book on Zora Neale Hurston as an anthropologist.