Americans love peanuts. We spend almost $800 million a year on enough peanut butter to make 10 billion sandwiches, and six of the top 10 candy bars contain peanuts or peanut butter.

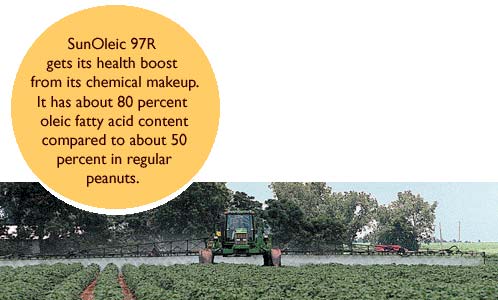

Now University of Florida peanut breeder Dan Gorbet has given consumers a reason to eat even more peanuts — a variety called SunOleic 97R that is richer in heart-healthy oleic fatty acids than olive oil. In addition, peanut growers should like SunOleic 97R because it yields more peanuts per acre and companies that use peanuts in their products should appreciate SunOleic 97R's longer shelf life. It still may be a few years before consumers find themselves checking labels to be sure they are getting high-oleic peanut butter and other peanut products on grocery store shelves, but Gorbet says, "Things are starting to come together to position ourselves in the world marketplace for high-oleic peanuts." The key to SunOleic 97R's potential lies in its chemistry. It has more than 80 percent oleic fatty acid — compared with about 70 percent in olive oil and 50 percent in regular peanuts. Fatty acids are a major component in all oils, but it is the oleic form — found in largest quantities in olive and canola oils — that scientists believe make them healthy. "This peanut has even more oleic acid than olive or canola oil," says Gorbet, who developed the peanut at the North Florida Research and Education Center in Marianna, a part of the University of Florida's Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. "Its health benefits, therefore, could potentially be better."

Florida's high-oleic peanut is hitting the market just as peanuts are coming back into vogue as a health food. There have been numerous studies in recent years touting the health benefits of peanuts. A study published in the Journal of Obesity last October by researchers at Harvard University and Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston found that people who incorporated peanuts into a "Mediterranean-style" moderate-fat diet were much more likely to stick to their diet than people who restricted themselves to a low-fat diet. Another study published in the December 1999 American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that diets higher in monounsaturated fat from peanuts, peanut butter, peanut oil and olive oil reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease by 21 percent compared to the average American diet, whereas a low-fat diet reduced the risk by only 12 percent. In a 1995 study at the University of Florida, the HighOleic 97R peanut's chemistry, in conjunction with a low-fat diet, was shown to help reduce coronary risk factors by lowering blood cholesterol levels in postmenopausal women. That study, conducted by IFAS nutrition Professor Rachel Shireman, showed significant reductions in serum cholesterol and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol — the so-called "bad" cholesterol. The study, published in the scientific journal Lipids, concluded that substituting high-oleic peanuts as the primary source of monounsaturated fatty acids in a low-fat diet may be more advantageous than use of typical vegetable oils. "The picture is becoming more and more clear that monounsaturated chemistry is the key to good heart health," says Gorbet. "Peanuts already had good oil chemistry, but with the enhanced high-oleic qualities, this improves peanuts a quantum leap." The advances have had a long road to the marketplace, but the university realized the potential of the new peanut early on and worked hard to secure the patent and reach favorable licensing agreements, says Bruce Clary of the University of Florida's Office of Technology Licensing. "The goal is to make it as easy as possible for the industry to embrace the high-oleic acid trait of this peanut," says Clary, who shepherded the high-oleic peanut applications through the United States Patent Office. Sunflowers Block The WayFlorida first applied for a patent on the high-oleic peanut in 1987 and expected a normal two-year wait for the patent to be approved. "Our patent applications pended for 12 years," Clary says. The SunOleic peanut and a high-oleic sunflower were breaking new ground on the patent front. Clary said the patent office had not seen an application for a utility patent on a naturally occurring plant until it received one for a high-oleic sunflower — just ahead of UF's patent application for the high-oleic peanut. The patent office put Florida's application on hold while litigation over the validity of the sunflower patent made its way through the courts. Ultimately, the courts ruled that the sunflower patent was valid, clearing the way for Florida's patents on the peanut plant lines, products made from the peanuts and the peanut oil.

Rather than being a frustration, the delay proved to be fortuitous, Gorbet says. An earlier version of the high-oleic peanut — SunOleic 95R — was going through trials just as the worst of a plant disease called tomato spotted wilt virus was sweeping the South. Since 95R was susceptible to the virus, it could not be grown in the Southeast, including the high production areas of Virginia and North Carolina. Texas appeared to be spared by the virus but didn't represent enough acreage on its own. "Tomato spotted wilt virus was a major impediment, not just for 95R but for other major varieties as well," Gorbet said. "And it was at its peak." So, while waiting for the patents to clear, Gorbet went back to the laboratory and developed SunOleic 97R, which kept all the good traits of 95R and added resistance to the virus. SunOleic 97R also has a greater yield, offering growers 10 to 14 percent more peanuts per acre than the industry standard, Florunner, which was also developed by UF in the late 1960s. In addition, SunOleic 97R offers a three- to 16-fold increase in the shelf life of the peanut. Traditional ScienceGorbet says that unlike some newer crops that have been genetically engineered, nothing so high-tech took place in developing the high-oleic peanut. "There is no molecular manipulation involved in this process at all," Gorbet says. "It's all conventional breeding." Three decades of conventional breeding, that is. In 1970, Gorbet began identifying peanut varieties with different beneficial attributes, like oleic acid content and resistance to wilt virus, and crossbred them to achieve the optimum attributes. Those plants were then used to produce the seed that grows the peanuts for sale.

"The confectioners see a lot of advantages in the high-oleic peanut because of the extended shelf life," says Bob Parker, vice president for procurement at Golden Peanut Co. in Atlanta, one of the country's largest peanut processors and one of the licensees for SunOleic 97R. Gorbet says the longer shelf life translates into millions of dollars of savings on recalls due to outdated product. "In industry meetings, where many varieties of peanuts are handed out and tested by growers and manufacturers, this is the peanut everyone's eating," he says. With consumer demand, the acreage planted in SunOleic 97R peanuts in the United States could triple, Gorbet says, especially with the high-oleic peanut's potential as an oil crop. High-oleic peanuts share the healthy oil chemistry of olive oil — possibly even having an edge on olive oil — and that trait could lead to a 50 percent increase in consumption in the United States, Gorbet believes. "I hope the industry recognizes the opportunity it has now," Gorbet says. "We're ahead of the world in this technology, we're established as the go-to place for this type of peanut. We're in a position to supply the best peanuts anyone can buy in the world."

Daniel W. Gorbet

|

||||||||

"Patents that should have been issued in 1988 or so actually were issued in 1999-2000," Clary says. "But that extends our patents through 2016."

"Patents that should have been issued in 1988 or so actually were issued in 1999-2000," Clary says. "But that extends our patents through 2016."

Because peanut shellers, who buy raw peanuts from thousands of growers and prepare them for the commercial market, will have to pay a premium for SunOleic 97R and be willing to keep high-oleic peanuts segregated from regular peanuts during processing, the key to the success of SunOleic 97R will lie in creating demand for its beneficial traits, Clary says. While consumers may be most interested in the health benefits, manufacturers will likely have just as much interest in the peanut's long shelf life.

Because peanut shellers, who buy raw peanuts from thousands of growers and prepare them for the commercial market, will have to pay a premium for SunOleic 97R and be willing to keep high-oleic peanuts segregated from regular peanuts during processing, the key to the success of SunOleic 97R will lie in creating demand for its beneficial traits, Clary says. While consumers may be most interested in the health benefits, manufacturers will likely have just as much interest in the peanut's long shelf life.