|

|

University Of Florida And Florida State University Researchers Take A Hard Look At

|

|

|---|

Kiser, former Democratic Gov. Buddy MacKay and other members of the institute’s board of trustees are promoting Tough Choices as the starting point for a dramatic reassessment of how Florida will provide for its residents in the future.

Tough Choices is arguably the most comprehensive look forward on many fiscal issues in more than two decades.

“You could fill a bookshelf with the many reports that have analyzed Florida’s tax system and argued for change,” Kiser wrote in an op-ed promoting the report. “Those studies are useful but one dimensional. This study looked at both revenues and government services — what the government takes in and what it provides to the people.”

The trustees contributed a half-dozen recommendations to the voluminous research, starting with the formation of a new state commission to continue the work the institute started.

Collins Institute trustees hope that as a privately funded effort through a bipartisan organization, the report is less likely to be “dead on arrival” in the state Capitol.

“This work began as an analysis of revenue and public service trends in Florida,” the report’s summary says. “It remains just that — NOT back-up documentation for a pre-set pet reform proposal of ours.”

|

|---|

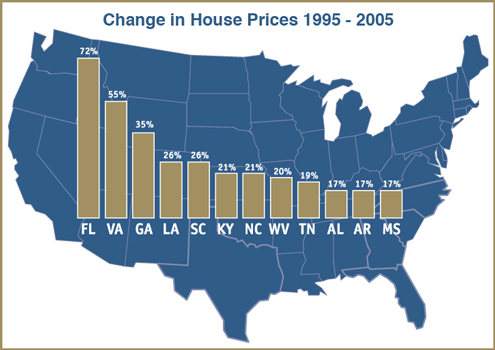

| Over the past decade, adjusted for inflation, house prices have risen by 72 percent in Florida. Houses now cost more in Orlando or Sarasota than in Atlanta. Among Southeastern states, the next highest increases were 55 percent in Virginia and 35 percent in Georgia.

Source: Repeat-Sales Index, Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight. |

Boom Time

By any measure, the current real estate boom has been impressive. Between 1996 and 2004, housing prices rose 70 percent, compared to 50 percent nationally. That’s compared to a 7 percent decrease from 1980 to 1996.

“One major consequence of the boom is soaring revenue for Florida’s state and local governments,” Denslow writes. “Housing construction boosts sales tax revenue as builders buy lumber and concrete and as owners buy new furniture, curtains and mailboxes.”

Another telling example: In just four years revenue from the state’s documentary stamp tax on real estate transactions tripled, from $479 million in 2001 to $1.5 billion in 2005.

“The revenue gains lead to the question of what to do with the money: Cut taxes and charges and fees? Increase the level of public services? Build infrastructure?” Denslow says. “In choosing the best mixture, it would help if we knew the future. Of course we do not. One thing that is reasonably certain is that the boom will end. What we do not know is when and how.”

The Collins Institute recognizes that predicting trouble in the midst of double-digit growth sounds “counterintuitive and alarmist,” but the report points to disturbing trends on the horizon, particularly education costs and Medicaid.

|

|---|

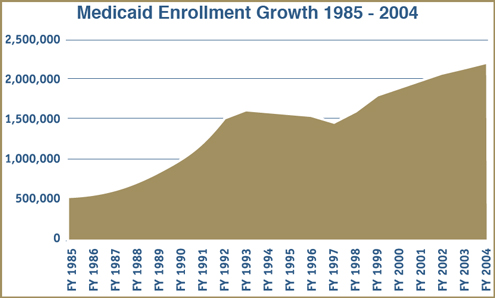

Medicaid growth has moderated some since the the late 1980s and early 1990s, but Florida experienced a nearly 10-percent increase in Medicaid expenditures in 2004-2005 and expects a 13.7-percent increase in 2005-2006. Source: Social Science Estimating Conference, Sept. 2003. |

Tough Choices was born out of conversations several years ago between Collins Institute Director Jim Apthorp and representatives of the Jacksonville-based Jesse Ball duPont Fund. duPont awarded the institute $100,000 to conduct a broad assessment of Florida’s economic future, then the institute’s board commissioned Denslow and Weissert to conduct the research.

In many ways, Denslow and Weissert were uniquely suited to the challenge of expanding the report beyond yet another ivory-tower exercise.

Denslow is a native Floridian and a member of UF’s College of Business faculty since 1970. He was chair of the Governor’s Council of Economic Advisers from 1987 to 1990 and sits on the Collins Institute board. Weissert is a newcomer to Florida, relocating to FSU as the LeRoy Collins Eminent Scholar Chair just three years ago from Michigan State University. She has published four books and dozens of articles on federalism and intergovernmental relations, state politics and public policy.

Revenue-Service Squeeze

|

|---|

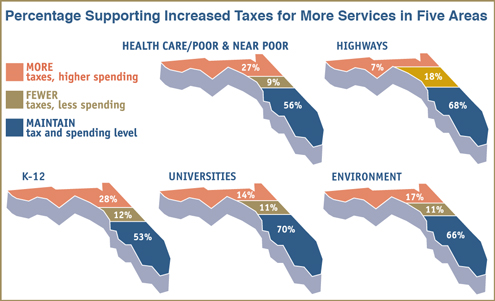

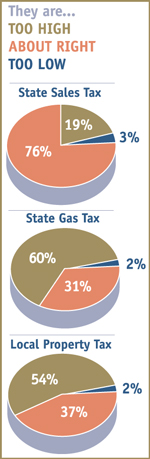

UF Bureau of Economic and Business Research surveys in May and June 2004 asked Floridians a series of questions about taxing and spending. Source: UF Bureau of Economic and Business Research, Survey May-June 2004. |

While the study was funded as a nonpartisan effort, no one involved has any illusions about its political implications.

“The revenue-service squeeze will be inherited by a new governor and new legislature in 2007, whoever they may be, whatever party, whatever their agenda,” the report says, referring to the gap between the money state government brings in and the cost of the services it provides.

Some of the Tough Choices findings are sure to trigger political early-warning radar. Gov. Jeb Bush has already pushed a Medicaid reform package through the Florida Legislature that will privatize much of the system. But even though Medicaid — which the report describes as an 800-pound gorilla — consumes more than 20 percent of the state’s budget, Florida’s spending per resident in fiscal year 2004 was 20 percent lower than the national average.

Tough Choices also addresses the impacts of Florida’s 5 million residents over the age of 55, including 3 million retirees, 10 percent of the nation’s total.

Retirees from New Jersey and Michigan save an average of $700 annually in combined income and sales taxes by moving to Florida, while retired New Yorkers save about $2,000 annually.

Denslow concludes 28 pages of analysis about retirees’ economic impact with this assessment: “They can raise their families in states that offer outstanding schools and universities then, when the children have left, retire to Florida and vote to limit funding for education and health care for other people’s children … even though their own children were well cared for with the support of the generation that preceded them, the greatest generation. The effect on the nation is not disastrous, but also not helpful and not Florida’s highest calling.”

Public education costs continue to soar, both pre-kindergarten through 12th grade and higher education, with politically popular programs contributing to those trends.

The report backs efforts by Bush and other state leaders to get the class-size amendment approved by voters in 2002 modified. A lengthy analysis by Denslow and his colleagues at UF’s Bureau of Economic and Business Research concludes that limiting class size has the greatest impact in the early grades, then falls off through middle and high school.

Meanwhile, the estimated $27 billion cost of implementing the class-size amendment is “all-consuming of available revenues, cutting off competing needs like raises to attract starting teachers,” the report says.

The report also looks at Florida’s Bright Futures program, which pays some or all of the costs of college for nearly a third of the state’s high school students. The program’s cost has increased five-fold since its inception, from $52 million for 26,240 students in 1997 to $263 million in 2005 for 125,101 students.

|

|---|

The public's percepion of Taxes |

Tough Choices also argues that “Florida has dug itself into a deep hole on basic infrastructure,” with an estimated $20 billion to $40 billion backlog just on roads.

“Nothing epitomizes infrastructure problems better than a traffic jam,” the report says. “In the end, though, Florida is faced with a whole lot of road building and widening in the coming years — and the necessity of do-it-yourself financing for a large share of that work.”

Children’s health services face similar challenges. There are long waiting lists for various health-care programs for children, and in 2002 Florida ranked 35th among the states in 10 key indicators of child well-being. The state ranked 36th in the percent of low-birth-weight babies and 32nd in infant mortality.

The few bright spots in the report are on welfare reform, prisons and protection of natural resources.

“Slowed revenue growth will challenge Florida to stay strong where it is strong and will put particular pressure on services like higher education and children’s health, where the effort is barely adequate at present,” the report concludes.

“Florida is at the bottom in virtually every area in spending: education, infrastructure, Medicaid,” says Weissert. “It looks like Florida has been hanging in there but if the housing boom starts to decline, there is going to be trouble.”

Research that gets Results

Elected officials generally have responded politely to the report, Kiser says, though many are incredulous that Florida needs more revenue, given the state’s current surging economic picture.

“The typical reaction was they grabbed ahold of items in the report on raising revenue and kind of said ‘Oh my God,’” says Kiser. “‘Yes, we are glad you did it,’ they seemed to be saying. ‘At least we have a benchmark for the state for what may happen in the future.’ But there was a hesitation to commit to formally institutionalizing the report.”

|

|---|

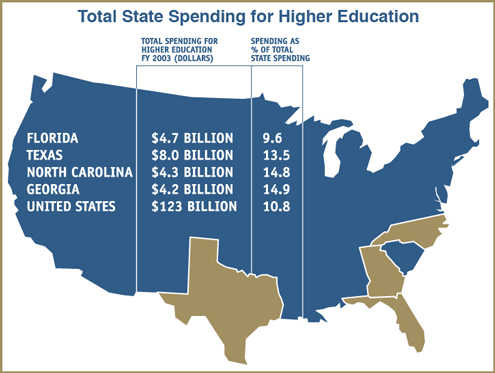

In FY 2003, Florida spent 9.6 percent of its total budget on higher education — lower than the national average of 10.8 percent and lower than every Southern state except West Virginia. Source: National Association of State Budget Officers, 2004. |

However, that time may come. If or when the revenue crunch hits, Tough Choices likely will become a high-profile reference. Until then, the Collins group is attempting to circulate the report to political leaders at a critical time.

“To get the general public aroused, you have to be really close to a situation occurring,” Kiser says. “It is just human nature. People are worried about getting up, making sure there is hot water in the morning, getting the kids off to school … Most people don’t have the luxury of reading the report beyond a capsule in the newspaper.”

Even if they did, that might not be sufficient to create action, suggests Dominic Calabro, president and chief executive of Florida TaxWatch, a watchdog group.

Questions of what’s to gain, what’s to lose, who pays and who benefits must be answered in simple terms so people can make informed decisions about what positions to support, Calabro says.

“In short, research must get results,” says Calabro, a Tough Choices advocate.

Well-informed, thoughtful citizens will disagree about how to deal with the structural issues, but the report gives academic credence to the arguments being made by numerous influential people and organizations, including TaxWatch, the Florida Council of 100 and advocates for everything from education to infrastructure, Denslow says. That adds a dose of realism to the debate.

“This occurs, fortunately in our view, as Florida’s politics is moving away from ideological extremes toward greater pragmatism,” he adds.

Leading or Following

|

|---|

Collins Institute Chair Curt Kiser (left), FSU political scientist Carol Weissert and UF economist David Denslow. |

In the Tough Choices conclusion, Weissert calls the study "in some sense a reaffirmation" of the findings two decades ago by the so-called Zwick Committee, a group mandated by the Florida Legislature to make recommendations about Florida's State Comprehensive Plan. The committee was headed by Charles Zwick, a former budget director in President Lyndon B. Johnson's administration who was credited with balancing the federal budget.

But Zwick -- the retired chairman of Southeast Bank in Miami -- takes issue with a core principle of the Tough Choices report, articulated in its introduction: "Florida's system of governance, including its taxing and spending, should reflect the desires of its citizens."

"Are you leading or following on the state level?" Zwick asks.

"The new report has lots of good data," he continues. "My question is what is the role of government -- to lead or to follow? We took as a given (in the Zwick Report) that the key to Florida's future is to win in a competitive world."

Zwick believes Florida has simply "muddled through" without a long-term vision since his committee completed its work.

Another advocate for even stronger positions is MacKay, who served in the Florida Legislature in the late 1960s and early '70s before being elected to three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. Later, after serving as Florida's lieutenant governor, MacKay served as governor for about a month after Lawton Chiles died in office.

MacKay wants the state's growth to pay for itself, but since individual counties rather than the state set impact fees they vary widely from place to place. That usually results in subsidies for newcomers and benefits for residents whose incomes depend on growth, MacKay believes.

"I used to say to Lawton Chiles all the time, the state can sell quality as well as it can sell tackiness," MacKay says, pointing to places like Boca Raton and Naples that have boomed despite high impact fees.

"I am pleased we got adequate funding to get the two best researchers in the state," MacKay says of the Tough Choices report. "But I am among those in this bipartisan group who believe we did not go far enough."

Ted Jackovics is a business reporter for The Tampa Tribune.

David Denslow

Distinguished Service Professor, UF Department of Economics

(352) 392-0171

denslow@bebr.ufl.edu

Carol S. Weissert

LeRoy Collins Eminent Scholar Chair, FSU Department of Political Science

(850) 644-7320

cweisser@fsu.edu

Related Web Sites

http://www.fsu.edu/~collins/