Ditch Of Dreams

By Joseph Kays

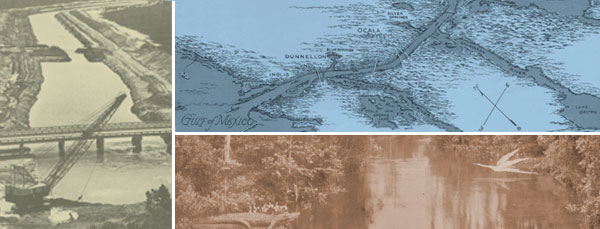

A new book chronicles the history of the Cross Florida Barge Canal and the role UF faculty played in the fight against it

Imagine Ocala as one of the commercial centers of the United States, indeed the world. Imagine Palatka as Disney World.

Now imagine turning the tap on your kitchen sink and getting salt water. Or imagine the primeval Ocklawaha River’s serpentine curves carved into an arrow-straight aqueduct filled with diesel-belching freighters.

Such were the competing visions of Florida throughout most of the 20th century as commercial and conservation interests waged war over the construction of a canal across Florida from the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico.

The canal, which was first proposed by the earliest Spanish and English settlers as a shortcut around the long and dangerous ship routes through the Florida Straits, dominated Florida politics from the 1920s through the 1990s. And remnants of the project continue to prompt debate today.

Like most Floridians, University of Florida history Lecturer Steve Noll and Santa Fe College history Associate Professor David Tegeder knew little about the canal when they were asked to write about its history as part of a report the UF College of Design, Construction and Planning had been commissioned to produce for the Florida Division of Greenways and Trails.

Seven years and thousands of hours of research later, Noll and Tegeder have produced the first comprehensive story of the canal in Ditch of Dreams: The Cross Florida Barge Canal and the Struggle for Florida’s Future published in October by University Press of Florida.

“Our research about the Cross Florida Barge Canal was not just another investigation of the past, for the canal and its history are central to the understanding of modern-day Florida,” Noll and Tegeder write in the book’s introduction. “The story of the canal reveals much about the competing visions of progress and preservation in Florida.

“The history of the Cross Florida Barge Canal, therefore, is not just another story about modern Florida — in many respects it is THE story of modern Florida. As Floridians struggle with concerns about growth and preservation in a fragile and increasingly finite environment, the almost 200-year legacy of this project looms as a cautionary tale over present-day public policy discussions concerning transportation and water use.”

With meticulous attention to detail, Noll and Tegeder chronicle the constantly shifting sands of state and federal politics as boosters and opponents of the canal vie for supremacy.

“We could have written this book just from the headlines in local newspapers,” Tegeder says, “but we wanted to dig deeper and get the whole story.”

With more than $50,000 in funding from the Division of Greenways and Trails, the pair scoured archives from Hyde Park, N.Y., to Washington, D.C., to Tallahassee in search of the little details that reveal the true story of the canal.

Burying The Depression

With the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914, north Florida canal boosters had a shining example of the economic benefits the state could reap by shortening the route from the oilfields of Texas and the great north-south highway of the Mississippi River to the industrial East Coast.

“As part of a network of artificial waterways that not only reached into the interior but hugged the Gulf and Atlantic shorelines, a Florida canal promised to become the lynchpin of a national transportation system,” Noll and Tegeder write.

With the support of President Theodore Roosevelt, in 1909 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers embarked on a comprehensive survey of potential canal routes, all the time being lobbied by groups with a vested interest in one route or another, from St. Mary’s Ga., as far south as Lake Okeechobee.

After years of research and consideration of 28 potential routes, in 1933 the Corps finally settled on a route known as 13-B that called for a 35-foot-deep, 250-foot-wide cut that would allow ships to utilize the existing St. Johns, Ocklawaha and Withlacoochee rivers to cross the state.

The selection of Route 13-B came just as President Franklin Roosevelt was ratcheting up public works projects to put the millions of Americans unemployed by the Great Depression back to work.

After considerable lobbying by such Florida political heavyweights as Duncan Fletcher and Henry Buckman, Roosevelt authorized the first $5 million for construction to begin.

On September 19, 1935, President Franklin Roosevelt, linked by telegraph from Hyde Park, set off 50 pounds of dynamite to inaugurate the project at a point about two miles south of Ocala on the old Dixie Highway, today known as U.S. 441.

“Touted as the greatest moment in not just Ocala’s, but the state’s, history, the ceremony was filled with pageantry and color,” the authors write.

With thousands of recently unemployed bricklayers and carpenters at its disposal, the Corps of Engineers was able to make impressive progress.

“Two weeks after construction began,” the book says, “a reporter announced that ‘more than 1,500 workers on the Gulf-Atlantic ship canal buried the depression here today as clinking cash registers rang out a lively tune.’”

Most of the workers lived in Camp Roosevelt, a temporary city constructed just south of Ocala. Relying primarily on newspaper reports, Noll and Tegeder describe in detail how the launch of the project impacted the region.

“New restaurants, hotels and theaters quickly opened as business increased between 25 and 50 percent,” according to the book. “In one county meeting, 10 applications for liquor licenses appeared on the agenda.”

But the canal had the biggest impact on the unemployed. By mid 1936, more than 6,000 men had been recruited from Florida’s relief rolls.

“Without a hint of exaggeration, the Tampa Tribune reported ‘there is not a single unemployed person in Marion County today.’’

But even as land was acquired and work began, opposition to the canal was mounting, in Florida and around the nation.

At home, agricultural interests continued to raise concerns about the canal’s impact on the Florida Aquifer, and the potential to allow saltwater into the state’s freshwater drinking and irrigation supply.

Nationally, conservative legislators from other parts of the country, led by Michigan Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg, questioned the cost and benefit of the canal and stalled further funding.

Roosevelt, for his part, was disinclined to expend political capital on a project that did not even have unanimous support in Florida so in 1936, when the U.S. House of Representatives voted to discontinue funding for the canal, work stopped immediately, Noll and Tegeder report, and “Ocala’s boom quickly came to an end.”

With the advent of World War II, supporters tried to use a national defense argument to renew funding for the project, and when a German U-boat torpedoed an oil tanker within sight of Jacksonville, they thought the case was made. But as it became clear that the canal could never be built in time to benefit the war effort, yet another argument in its favor faded.

Throughout the 1950s canal supporters tried to maintain a presence in Washington despite a general lack of interest from Congress or the White House.

During the intervening years the canal had been scaled back from a 35-foot-deep ship canal to a 12-foot-deep barge canal, muting protests about its threat to the aquifer, so supporters thought they had answered all the opponents’ concerns.

When Democrat John Kennedy was elected in 1960, the pro-canal forces sensed an opportunity.

Kennedy had supported the canal during the campaign and, true to his word, shortly after taking office authorized $195,000 to conduct a new cost-benefit analysis of the revamped barge canal. Despite their claims about the economic benefits of the canal, supporters had always had a hard time proving that the canal would provide a positive return on the government’s investment. Finally, a June 1962 report got the benefit marginally over the cost, blunting criticism that the project was a boondoggle.

Under more heavy lobbying pressure from Florida’s Congressional delegation, Kennedy included $1 million for canal construction in his 1963 budget request and two days before his assassination the House of Representatives passed the funding measure.

On February 27, 1964 President Lyndon Johnson attended the official groundbreaking, of what the Corps of Engineers called the “century-old dream of a waterway across the upper neck of Florida,” Noll and Tegeder write.

Having answered all the engineering challenges and with funding secured and a supportive administration in Washington, canal supporters finally thought the way was clear for the completion of the long-anticipated canal.

Micanopy Housewife

What canal supporters had not counted on, however, was what Noll and Tegeder call “a new calculation in the building process — the value of nature itself as an irreplaceable entity.”

And that new element was embodied in a woman who was derided by canal supporters as “a mere Micanopy housewife,” but who would become one of Florida’s most recognized environmental champions.

Prior to her involvement in the canal debate, Marjorie Harris Carr was best known as the wife of the University of Florida’s most celebrated faculty member, Archie Carr, whose research and writings about sea turtles had made him an international figure.

Carr, who had earned a bachelor’s degree from the Florida State College for Women and then pursued a graduate degree at the University of Florida, had suspended her formal scientific career to raise her family, but “she remained a scientist at heart,” Noll and Tegeder write.

A year before the groundbreaking, “Carr and other north Florida residents started to weigh the consequences of construction” on the pristine Ocklawaha River.

Carr and UF biochemistry Professor David Anthony organized a meeting in Gainesville in November 1962 at which two state officials “gave a presentation on ‘the effects of the proposed cross-state canal on wildlife and wilderness areas’ as well as ‘the economic possibilities of such a canal.’”

“In spite of their arguments, accompanied by ‘impressive charts, statistics, and figures,’ most of the nearly 200 audience members remained skeptical,” the book reports.

“Energized by the level of discussion, Carr came away feeling that she had to do something” to save the Ocklawaha, Noll and Tegeder write. “Combining an almost mystical love of wilderness with a scientist’s understanding of ecology, Carr had found her calling.”

The authors maintain that the ensuing battle to first change the route and ultimately halt canal construction could not have succeeded without Carr’s University of Florida connections.

“It would have been extraordinarily difficult to stop the completion of the barge canal without the university,” Noll argues. “The University of Florida provided the scientific and economic rationale for rebutting and debunking all of the Army Corps of Engineers’ and the Canal Authority’s beliefs and understandings about why this would be good for Florida.

“UF becomes the center of opposition to the barge canal in the 1960s,” he adds. “Marjorie Carr enlists a whole cadre of UF faculty in fields like chemistry and economics to come up with the scientific rationale for why the canal is a bad idea.”

The noise being made by the Citizens for Conservation group Carr and Anthony started, “invited ridicule, as best, and, at worst, outright hostility” from canal supporters, according to the book.

“What this corporation in Gainesville does is of no concern to me,” Lake County Congressman Sydney Herlong wrote in 1965. “The canal is on its way to being built.”

But Herlong and others greatly underestimated Carr’s and the country’s emerging environmental ethos, Noll and Tegeder argue. In April 1965 the Florida Audubon Society announced its opposition to the canal and in July The New York Times published an editorial critical of the project.

“The Times argued that ‘it is time to stop the work and weigh the total public interest in the Ocklawaha before irreparable tragic damage is done to this stream for benefit of a project of what is, at best, dubious merit.’”

Over the next five years, Carr and others, backed by UF’s scientific experts, rode the wave of the emerging environmental movement to try to thwart the canal.

But despite their efforts, land acquisition and construction continued. By the end of 1966, the canal authority controlled 33,000 acres of right-of-way and locks on the St. Johns River and at Inglis near the western terminus of the canal were almost complete.

Then, in April 1967, the Corps of Engineers proudly introduced a new tool to clear the terrain.

“The dry statistics of canal construction belied the reality of the environmental destruction taking place in the Ocklawaha Valley,” Noll and Tegeder write. “Particularly invasive and especially visible when compared to the traditional use of draglines, bulldozers and cranes was the specially designed crusher.”

The 22-foot-high, 300-ton amphibious machine “quickly became the symbol of both the canal’s promise and its problems” as it cleared the land for the planned dam on the Ocklawaha that would supply the water to fill the lock between the St. Johns River and the Ocklawaha.

“Moving through the heavily timbered lowlands of the Ockla-waha Valley, the crusher cleared the terrain at the rate of one to two acres per hour,” the book reports. “Observers noted how the ‘newly developed mechanical marvel … mows down trees and pushes them underground as though they were matchsticks.”

“Ironically, it was the success of the Corps and the crusher’s destructive power that gave Carr an opportunity,” Noll and Tegeder write. “The extraordinary devastation wrought by the machine provided critics with vivid visual evidence of the destructive path of progress.”

The authors write that “nearly everyone who encountered the Rodman Reservoir of the late 1960s commented on the environmental destruction wrought by the crusher,” especially when the trees the machine had supposedly buried forever in the mud began to pop to the surface with alarming regularity.

In January 1969, NBC News invited David Anthony, who had become a key spokesman for the anti-canal movement, to join one of its crews on the river. Subsequent stories in Sports Illustrated and Reader’s Digest raised the national profile of the battle even higher.

“Complementing Carr’s strengths, David Anthony provided a quiet dignity that translated into frequently sabre-like sentences about the intelligence, if not the veracity, of officials in the Corps of Engineers,” the authors write. “As a University of Florida biochemist whose research experience reached back to the Manhattan Project, Anthony proved an unimpeachable source.”

Despite the growing opposition, bureaucratic inertia seemed destined to push the project through to completion, until Florida Defenders of the Environment, the successor to Citizens for Conservation, teamed up with the national Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) to pursue a legal remedy.

Relying on Anthony’s scientific arguments to win the day in court, EDF filed a lawsuit in U. S. District Court for the District of Columbia seeking temporary and permanent injunction against the construction of the canal.

On January 16, 1971, the court agreed, and five days later President Richard Nixon ordered the project scrapped, saying “The step I have taken today will prevent a past mistake from causing permanent damage.”

Lasting Legacy

Although the canal was not officially deauthorized for another 20 years, construction ceased immediately and the forest quickly began to reclaim many elements of the canal that had already been built.

As the construction phase of the canal controversy ended, a new question arose: What to do with the tens of thousands of acres of land acquired along the route.

Ultimately, the state decided to designate the land that opponents argued was being acquired for an environmental disaster into a 110-mile-long linear park that offers extensive recreational activities, including canoeing, biking and hiking. A year after Carr’s death in 1997, the Florida Legislature renamed the land the Marjorie Harris Carr Cross Florida Greenway.

“The establishment of the Marjorie Harris Carr Cross Florida Greenway turned the centuries-old boondoggle of a canal into a model conservation project,” Noll and Tegeder conclude. “Politics, science and economics are deeply embedded in the story of the Cross Florida Barge Canal and its important place in Florida’s history. The story is so compelling because Florida’s past is at once its future — as the questions raised by the canal and its legacy continue to persist.”

*Ditch of Dreams can be purchased through University Press of Florida, online at ufp.com or by calling 1-800-680-1955.

Steven Noll

Senior Lecturer, Department of History

(352) 273-3380

nolls@ufl.edu

David Tegeder

Adjunct Professor, Department of History

(352) 392-0271

dtegeder@ufl.edu

related link:

www.DitchOfDreams.com