|

downloadable

pdf

Catfish are found on every continent except Antarctica. They

range from fingernail-length miniatures to sedan-length monsters.

They are among the most diverse and common fishes, comprising

one in four freshwater species.

Despite nearly three centuries of exploration and research

and the recognition of more than 2,700 species, an estimated

1,750 catfish species remain unknown to science. But not for

long. Backed by a $4.7 million grant from the National Science

Foundation, scientists at the University of Florida’s

Florida Museum of Natural History have begun leading a five-year

effort to discover and describe all catfish species. The only

one of four similar projects in the NSF’s Planetary

Biodiversity Inventory program that focuses on vertebrates,

the project will tap 230 scientists from around the globe,

with many hauling nets and buckets into some of the world’s

most remote waters. The other NSF projects focus on plants,

insects and microscopic organisms called Eumycetozoa or, more

commonly, slime molds.

|

SOME

CATFISH BREATE AIR AND SQUIGGLE ACROSS LAND. OTHERS

STUN PREY WITH SHOCKS REACHING 400 VOLTS. STILL OTHERS

SUBSIST ON WOOD LIKE TERMITES

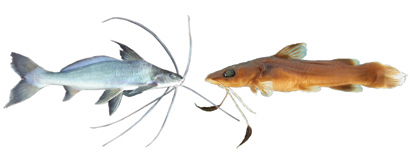

above: Pinirampus pirinampu and Phyllonemus typus, below:

Bagre bagre and Pseudacanthicus leopardus |

|

Practical

considerations have long forced scientists to limit investigations

to small geographical areas or a few species at a time. The

Planetary Biodiversity Inventory seeks to turn this tradition

on its head, shooting for the discovery and description of

all species within certain groups. Jim Woolley, program director

of the NSF’s biodiversity surveys and inventories program,

says the goal is a comprehensive accounting before it’s

too late.

“I think it’s clear to people that we are losing

habitats and losing biodiversity much faster than we can get

a handle on it,” he says. “We want to greatly

stimulate the rate and pace at which species discovery is

being conducted. This program was designed to tackle projects

on a scale never before attempted.”

The University of Florida-led project is headed by Larry Page,

an adjunct curator of fishes at the Florida Museum of Natural

History and principal scientist emeritus at the Illinois Natural

History Survey.

“Larry and the other principal investigators were clearly

in a position to pull this off,” Woolley says. “It

was clear that they had really drawn the community together

and that they were in a position for some very efficient and

effective collaborations.”

The Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, the California

Academy of Sciences, Auburn University and Cornell University

are the project’s other principal participants.

Species Surprises

|

| Larry Page

gets nose to nose with a catfish along guyana's Potaro

River |

By linking scientists and databases via the Internet, the

project will combine modern computer and communications technology

with hands-on collecting expeditions. Page and the other administrators

will distribute small grants, usually no more than $3,000,

to affiliated scientists worldwide for research either on

unclassified specimens housed in museums or on expeditions

to hunt for new species.

Both avenues are expected to bear fruit in the form of peer-reviewed

publications describing new species. Surprisingly, it’s

not always the dustiest museum specimen or most remote waters

that yield the best finds.

Six years ago, Rocio Rodiles was a doctoral student at the

Mexican research institute Eco-Sur working on her thesis research

to inventory all of the fish in the Lacantun River in southern

Mexico near the Guatemala border. The Lacantun is a tributary

of the Usumacinta, which is very well studied because of its

geographic location at the junction of North and Central America.

Rodiles was fishing with hook and line when she reeled in

a large, greenish catfish she had never seen before.

“The first time I saw it, I didn’t know what kind

of catfish it was,” says Rodiles, now a post-doctoral

fellow at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.

The fish looked like it belonged to the ictalurids, the family

of North American catfish, but it had enough unusual features

— such as the large pores on its head — to prompt

Rodiles to take a closer look. When comparisons of the fish

with known species of catfish failed to produce a match, she

contacted University of Texas ichthyologist Dean Hendrickson.

Together, the two discovered other characteristics that seemed

to set the Chiapas fish apart from the ictalurids. For example,

it has six instead of seven or more pelvic fin rays —

the supporting, bony elements of fins — and a very different

pelvic skeletal structure.

Curiously, Rodiles and Hendrickson found that the fish didn’t

fit into any of the South American catfish families, either.

After several years of study and discussion, they and other

icthyologists are now leaning toward placing the catfish in

its own, entirely new family, says John Lundberg, curator

and ichthyology department chair for the Academy of Natural

Sciences of Philadelphia and co-investigator on the catfish

inventory. The catfish has enough evolutionarily primitive

features to suggest that it is only remotely related to North

American catfishes, he adds.

Rodiles’ discovery is unusual, in part because the area

where the fish was found is so well studied and in part because

biologists have already described most large fishes for the

simple reason that they tend to stick out more than others.

Indeed, Rodiles says, the indigenous people who live near

the Lacantun River were familiar with the Chiapas catfish,

which they called “bagre,” as a so-so dinner entrée.

Catfish inventory researchers expect that most new species

they find will not be so distinctive, with some only identifiable

through obscure differences such as the placement of certain

bones.

Nevertheless, Lundberg wouldn’t rule out other such

major finds during the inventory. “Most of the new fish

we find will not have a very large body size, and some of

them are going to look like catfish species that we know,

but there’s always a chance of getting something highly

unusual,” he says.

Scientists are planning expeditions in South America, Asia

and Africa, which together are home to the bulk of the world’s

catfish. Destinations include rivers and streams in such forbidding

locales as Angola, Myanmar and Congo.

“The Congo River in Africa is very poorly collected

because it’s very difficult to get in there due to the

civil war, and because of the crocodiles,” Page says.

“But we’re making the contacts there, and we plan

to go in.”

Scientists use several techniques to collect fish specimens.

Probably the most common is netting, with nets ranging from

simple dip nets and large seines that several researchers

haul through the water at once to gill nets. Others include

“electrofishing,” or delivering an electric current

to the water to stun fish to the surface, and line fishing

with trot lines or similar methods. All are used for catfish,

but the fish are often nocturnal, so researchers will often

have to work at night, Lundberg says.

|

|

It

takes teamwork to catch these catfish,

says Larry Page, holding net. Some members disturb

the waters upstream, herding the fish

into the scientists’

waiting nets. |

Living

By Linnaeus

Famous University of Florida naturalist Archie Carr was once

quoted saying, “Any damned fool knows a catfish!”

And, indeed, scientists have an advantage in that nearly all

catfish are identifiable by their “whiskers,”

or barbels, their lack of scales and their adipose fin —

the small fin between their dorsal and tail fins. Beyond that,

they are incredibly diverse, incorporating almost every evolutionary

trick in the aquatic species repertoire. Some are armored

against predators. Others, having evolved in caves, are blind.

Some, inhabitants of fast-flowing streams in the Andes and

Himalayas, have modifications to their fins and mouths that

allow them to climb and hang onto vertical surfaces. Many

have venomous spines, which can deliver a painful and sometimes

dangerous toxin to predators or unlucky people. The tiny South

American catfish, the Candiru, which makes its living sucking

blood from the gills of bigger fish, has been known to squeeze

inside the orifices of unfortunate human swimmers.

Such is their diversity and abundance that “they work

as a surrogate for freshwater fishes,” Lundberg says,

explaining that catfish live in so many habitats and display

so many physical and behavioral modifications that they are

good representatives of freshwater fish in general.

|

|

| Nearly

all catfish are identifiable by their “whiskers,”

or barbels, their lack of scales and their adipose

fin — the small fin between their dorsal and

tail fins. Beyond that, they are incredibly diverse,

incorporating almost every physical trick in the

aquatic species repertoire. |

|

Catfish

predate many modern fish. They all belong to the order Siluriformes,

which falls into the biggest and most modern class of fishes,

the bony fishes. The most primitive living bony fishes, sturgeon

and paddlefish, originated in the Jurassic era 225 million

years ago. Catfish appeared well after, with the first fossil

catfish dating to the late Cretaceous about 70 million years

ago. That’s still millions of years before the advent

of most familiar fish such as grouper, members of the most

advanced order of fishes, the Perciformes.

From an evolutionary perspective, catfish have been enormously

successful, branching off into no fewer than 34 families found

in almost every freshwater habitat in the world. Their biodiversity

aside, that’s another reason they’re of interest

to scientists. Since all but a few species are confined to

freshwater, the distribution of the families and species allows

scientists to make inferences about how land masses shifted

over the eons.

“You can conduct biogeographic and other studies important

to understanding biological diversity on a worldwide basis,”

Page says.

More than two centuries ago, Carl Linnaeus pioneered modern

taxonomy, establishing the now-familiar zoological nomenclature

classing organisms into ever more defined and specific groups

of families, genera and species. Science has experienced unimaginable

transformation since Linnaeus’ era, but his taxonomical

system and the methods behind it have remained remarkably

unchanged. Linnaeus named the first few catfish in his new

system in 1758, including Siluris glanis, the Wels catfish,

Europe’s only native catfish and the world’s largest.

His methods — collection and preservation of the specimens,

careful examination of physical characteristics and comparisons

to similar specimens — will be the same ones used by

the biologists doing the catfish inventory.

At a time when genetics seems to hold the answers to all biological

questions, classic “morphological research” —

comparing the physical characteristics of fishes to determine

their similarities and differences — remains the most

efficient and practical method for new species discovery,

Page says.

“You can use genetic data, behavior, ecology, but really

it boils down to morphology,” Page says. “The

vast majority of individuals who will work with these fishes

in any context are going to use morphology — they have

to be able to recognize what they have.”

That includes Page, an expert on North American fishes and

author of the Petersen Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of

North America. For the inventory, he plans to travel to India

this spring to seek new species in Sisoridae, a family of

catfishes restricted to southern Asia.

“When we looked at all the participants in this project

and what they were working on, that catfish family in that

part of the world seemed the most poorly covered,” he

said. “We’re likely to discover a lot of new species.

It’s all going to be new to me, since I’ve never

been to Asia.”

Larry Page

Adjunct Curator, Florida Museum of Natural History

(352) 337-6649

lpage@flmnh.ufl.edu

Related Web site:

http://clade.acnatsci.org/allcatfish/

|