|

|

|

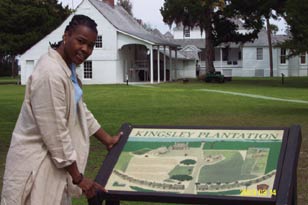

Antoinette

Jackson at the Kingsley Plantation on Fort George Island near Jacksonville.

|

Passion

Leads Doctoral Candidate to Explore Slave Life

After

earning a bachelor’s degree in computer science from Ohio State

University and an MBA from Xavier University, Antoinette Jackson had a

promising career as a business manager with Lucent Technologies/AT&T.

But

when she was recruited to pursue a doctorate in business, Jackson realized

that she didn’t want to spend the rest of her life in the business

world.

“Everybody

told me you have to have a passion for your subject to pursue a Ph.D.

and I just didn’t have that passion for business,” Jackson

says. “The more I thought about it, however, I realized that I did

have that passion for anthropology.”

During

the last four years, Jackson has pursued her passion by examining African

communities on and around plantations. She has specifically focused on

descendants of enslaved Africans and others associated with Snee Farm

Plantation in South Carolina and the Kingsley Plantation community in

Jacksonville, Florida.

Jackson,

who is also a McKnight Fellow, says she has always been interested in

plantation life from the African perspective, so she was thrilled when

she got an opportunity to study African communities associated with Snee

Farm Plantation, a former rice plantation currently maintained by the

National Park Service as the Charles Pinckney National Historic Site in

Mount Pleasant, South Carolina.

When

the National Park Service wanted someone to do an ethnographic study of

the Kingsley Plantation, they contacted the University of Florida’s

anthropology department based on previous research done at the site, most

notably by archaeologist Charles Fairbanks, and tapped Jackson’s

expertise based on her work in South Carolina.

|

|

An

artist’s rendering of Anna Kingsley |

“There

has been considerable archaeological research done at the Kingsley Plantation,”

Jackson says, “but very little has been done with families in the

community who are descendants of the Kingsleys and persons they enslaved.”

Jackson’s

research revolves around Anna Kingsley and her descendants. Anna, or Anta

Majigeen Ndiaye, was enslaved and purchased by Zephaniah Kingsley in Cuba

in 1806 when she was 13 years old. By the time she arrived in Florida,

she was pregnant with the first of four children she was to have with

Zephaniah Kingsley.

“The

central theme of the Zephaniah Kingsley story is his acknowledged spousal

relationship with Anta Majigeen Ndiaye, a West African woman described

as being of royal lineage from the country of Senegal,” Jackson

writes in a paper about the Kingsleys.

Zephaniah

Kingsley freed Anna Kingsley and their children from slavery in 1811,

and she managed much of the family’s interests and even owned slaves

herself.

After

Florida became a United States territory in 1821, treatment of slaves

and former slaves became increasingly oppressive. To protect his family

and his business interests, Zephaniah Kingsley moved Anna, the children

and most of his plantation operations to Haiti around 1837.

Zephaniah

Kingsley died in 1843 and Anna returned to Florida in the 1850s, living

in the Jacksonville area until her death in 1870.

“Anna’s

story is much different from the Thomas Jefferson/Sally Hemmings drama

that has come to typify master/slave/mistress relationships of the time,”

Jackson says. “She understood power very well, and more importantly

she understood how to manipulate power. Anna consciously used her knowledge,

her beauty and her position to secure a future for herself and her children.”

Jackson

says her research, much of it oral history, reveals that Anna Kingsley

“left a very precious legacy. She left children and grandchildren

who have gone on to contribute much to Florida life, history and culture,

and much to the history of Africans in America.”

The

Kingsley Plantation community today, Jackson says, “is embedded

in the fabric of everyday life in Jacksonville and the surrounding communities

in northeast Florida. It extends well beyond the Fort George Island site

to include all the places where Kingsley’s descendants or others

associated with the Kingsley community live or have migrated to.”

Jackson

says she hopes “to inform people, and make the plantation more real”

through her research, which she hopes will result in a book and an interpretive

display at the Kingsley Plantation site.

by

Joseph Kays

|